|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

September 15, 2022 | ISSUE 43 |

|

|

|

PlanetScope • Andes Mountains, Chile • June 14, 2022 |

In this week’s issue: Satellites observe Earth’s natural divisions; the Niger River winds its way through Africa; and an island re-emerges in Tonga. |

|

|

|

|

FEATURED STORYNatural Borders

If you’ve ever plunged into a lake, crossed over a mountain ridge, or dug a hole deep enough to hit bedrock, you’ve traversed one of Earth’s natural borders. These are places where two or more realms meet. But it’s rare for natural borders to have this type of sharp delineation, a feature shared with the political borders we covered a few weeks ago. In most cases, Earth’s edges are progressive, indefinite, and far more complex than a line separating two entities.

Earth’s borders are a bit like birthdays: certain points are marked but the overall change is gradual. Aging is a gradient, and where the sidewalk ends is still up for debate. While not political-map-sharp, these changes between Earth’s boundaries can still be pronounced. And the view from space reveals some fascinating insights into how these contrasting forces shape our world. |

|

SkySat • Agricultural fields (right) precipitously drop to a system of caves by the cliffs, which give way to forests in the Brazilian Plateau • March 26, 2022 |

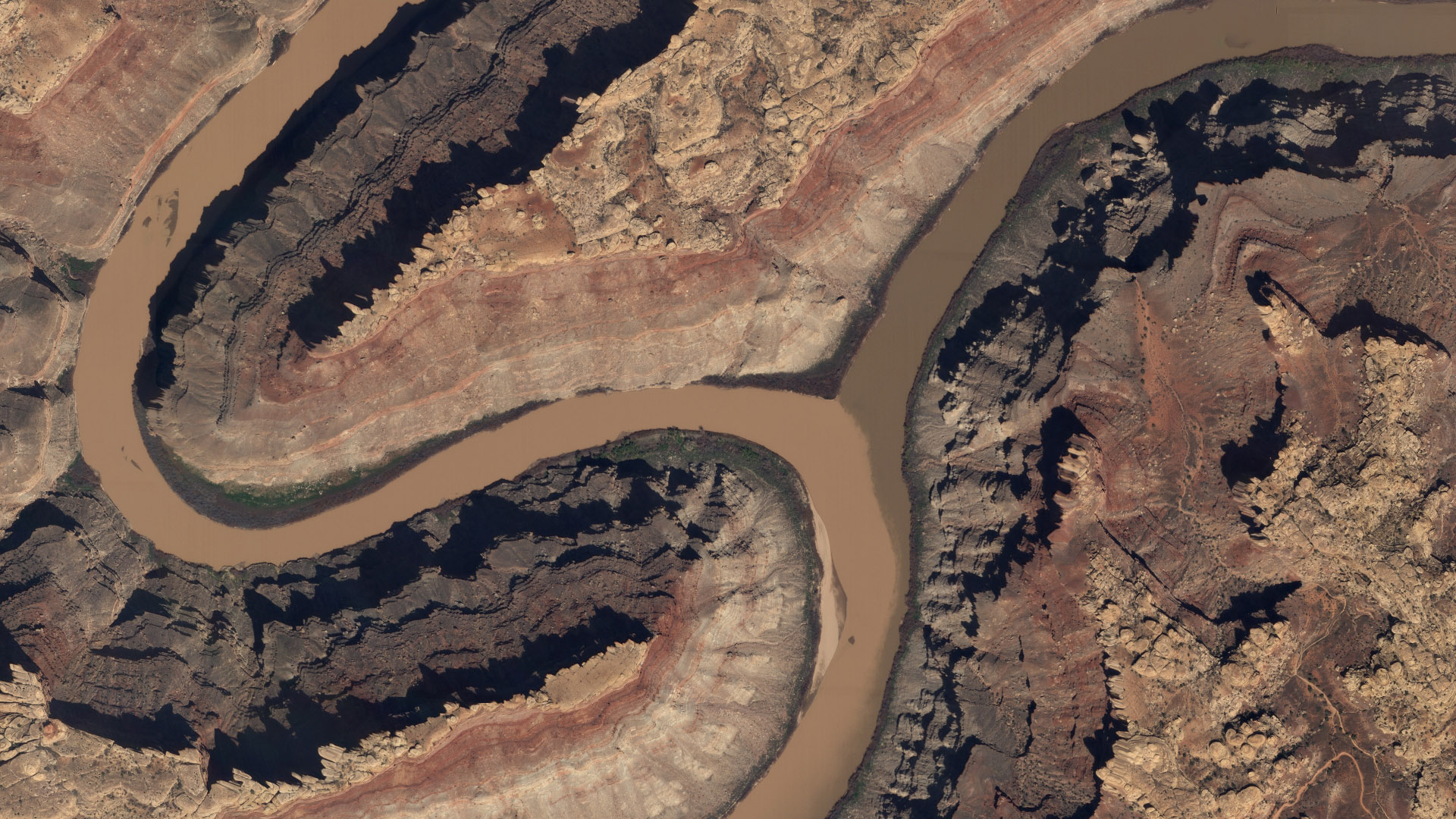

Natural boundaries can be as miniscule as sand grains touching ocean droplets to as large as the Sahel, the Africa-wide belt that separates the northern Sahara desert from the humid southern savannas. But because nature isn’t as tidy as we are when it comes to parceling out spaces, defining boundaries can be tricky. To simplify matters, we’re only going to be covering visual, mostly horizontal-oriented gradients on Earth’s surface, like the canyons cut by the Colorado and Green Rivers and their confluence. |

|

SkySat • Canyonlands National Park, Utah, USA • March 27, 2019 |

Rivers are one of the planet’s more pronounced divisions, making them good political borders as well. One study using NASA/USGS Landsat data found that rivers make up to 23% of international borders. They carve and divide the land over time and visually stand apart from their surroundings, like the Amazon River winding through dense rainforest or the Nile as it nourishes the land on its journey north to the Mediterranean Sea. |

|

PlanetScope • Nile River, Egypt • September 5, 2022 |

Earth’s version of a wall is a mountain range. And while that alone qualifies them as a natural border, some have a feature that particularly accentuates their division of the land. The gigantic peaks of the Himalayas stretch across 2,400 km (1,500 mi) of the Asian continent and separate the fertile plains of India from the arid Tibetan Plateau. This is called a rain shadow, and it occurs when mountains prevent rainy weather from reaching the other side. |

|

Planet Visual Basemaps • The Himalayas, Asia • April - June, 2020 |

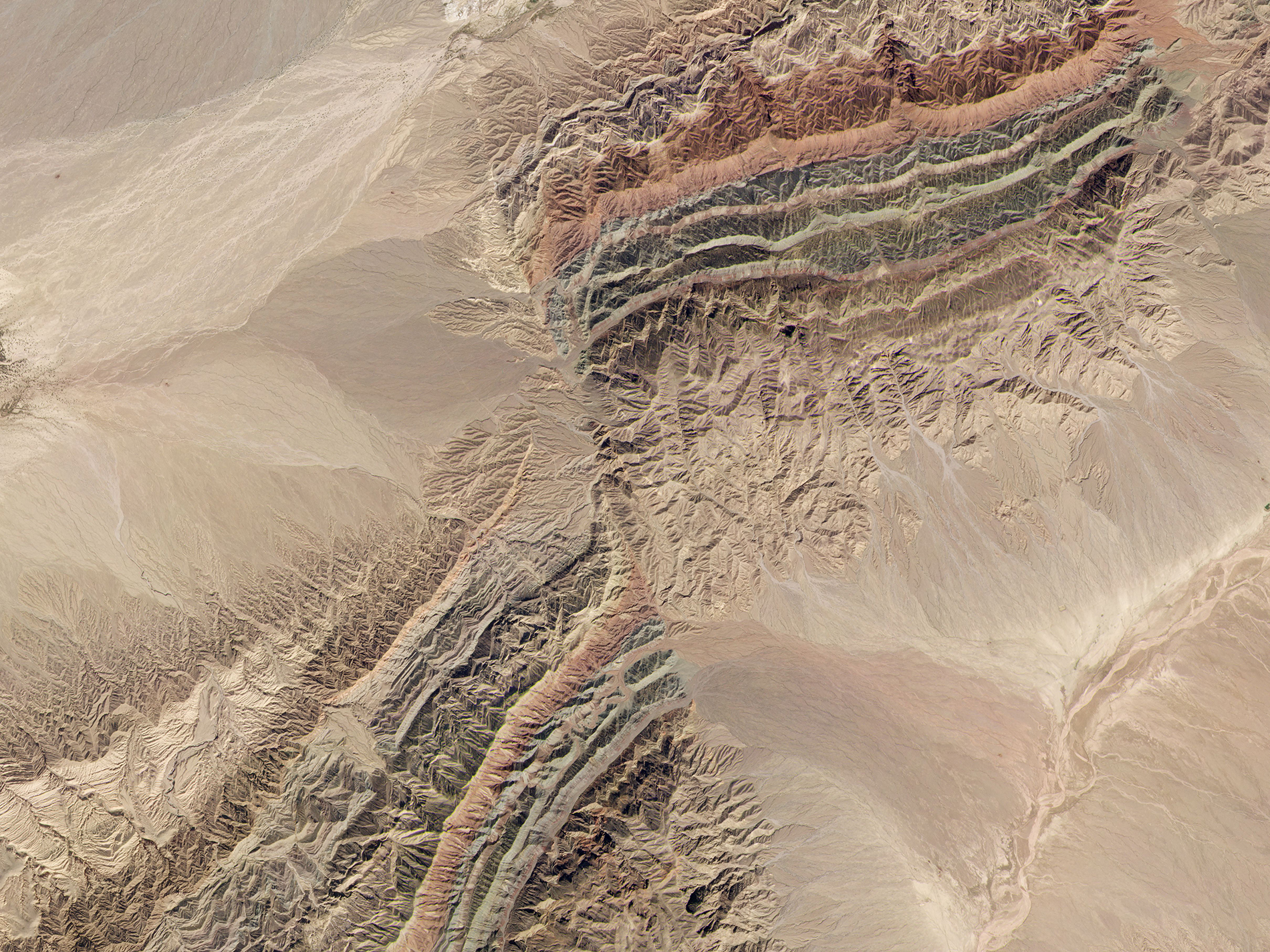

Of course, the whole reason why Earth has mountains is because of another edge case: plate tectonics. These rocky slabs on the planet’s outer shell slip 'n slide 'n shape the surface as we know it—creating a variety of borders both seen and invisible from space. Near the Tian Shan mountains in Central Asia, colored sedimentary rock is seen offset by a horizontal strike-slip fault, creating a near perfect straight line in the landscape. |

|

PlanetScope • Piqiang Fault, China • September 29, 2019 |

Like political borders, natural borders are more than just lines on the ground. They are sometimes ecotones, which sounds like an environmentally-forward pop band, but is actually a transitional area between two ecosystems. Ecotones are often more biodiverse than its two bordering areas and may be hotspots for creating new species. Vegetation belts can be seen on the rising slopes of Mount Kenya, with the varying ecotones being determined by altitude. |

|

|

PlanetScope • Mount Kenya, Kenya • May 24, 2022 |

Humans flock to Earth’s borders like ants to a pie (and ask any pie enthusiast and they’ll tell you its edges are best). It’s estimated that over 40% of the world’s population lives near a coastline, and that’s only one of many types of natural borders covering the planet. We’ve settled in, around, and among these contrasting topographies, but sometimes at a cost. |

|

PlanetScope • San Andreas Fault running top left to bottom right, outside of Bakersfield, California, USA • August 23, 2022 |

The problem—for us humans at least—is that the natural world’s borders don’t follow the same rules that ours do. Sea levels rise and push back coastlines, tectonic plates grind and shift land, rivers meander or dry up. In an attempt to take back control, we’ve begun ambitious terraforming projects, notably the creation of green belts and walls across the world. China is in the middle of a decades-long fight against desertification. They’re creating the Great Green Wall, a project that will plant millions of trees along their 4,500 km (2,800-mile) border with northern deserts. For desert-adjacent cities like Zhongwei, a complex tapestry of straw checkerboards is the only way to prevent nature’s march. |

|

PlanetScope • Zhongwei, China • July 4, 2022 |

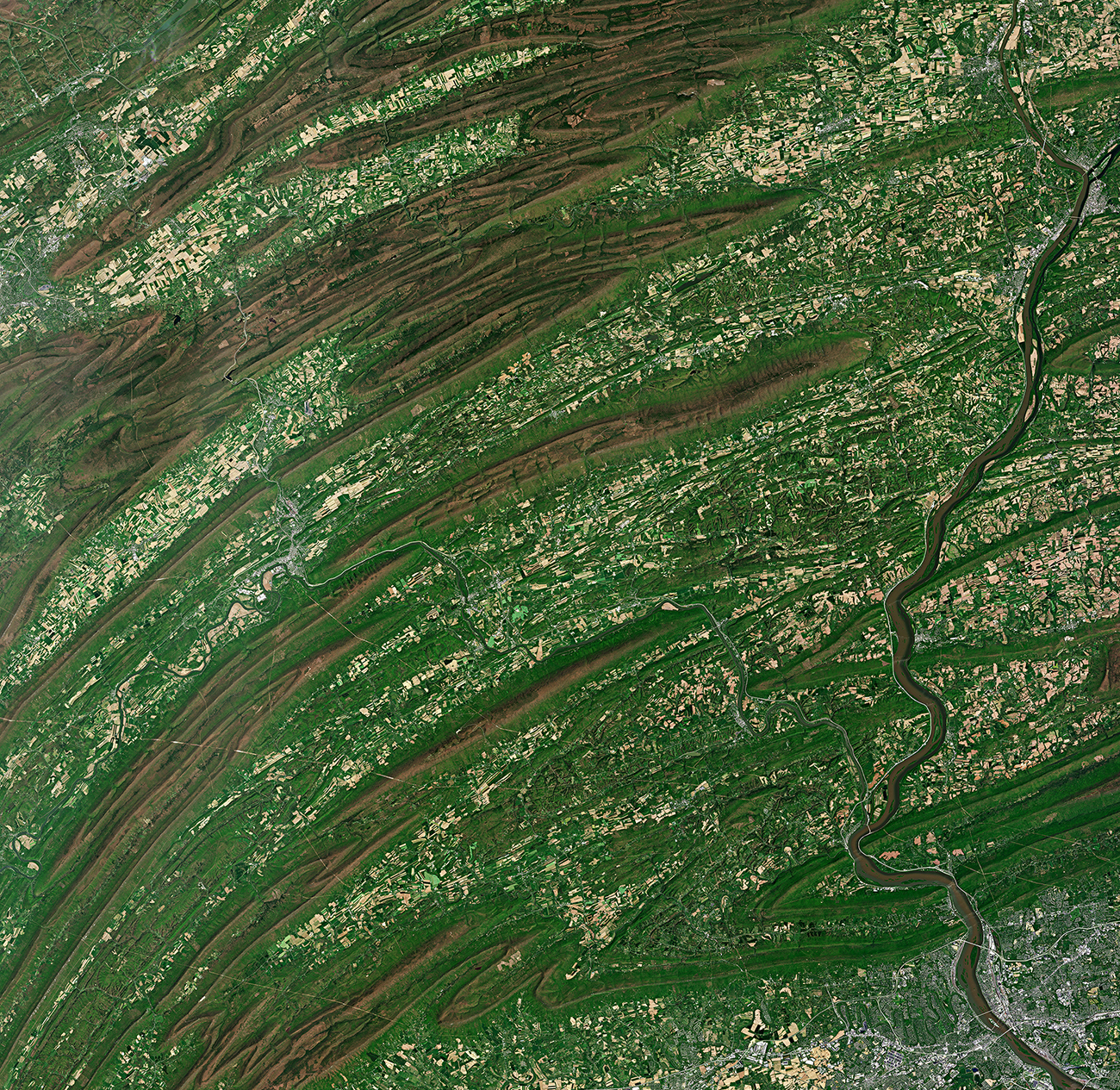

We draw lines on maps, then in the dirt, and then scramble to readjust when Earth invariably goes in a different direction. Political borders are stringent, natural ones are fluid. But the further we impact our environment and adopt nature’s boundaries as our own, the more we muddle the border between us and nature. |

|

PlanetScope • Farms, houses, and towns built around ridge folds near Lewistown, Pennsylvania, USA • May 10, 2022 |

Bonus: Harken back to the last issue where we shared 2 images of borders etched into the landscape via political protections. Well we couldn’t help ourselves from including another, ‘cause this one is special. Meet New Zealand’s Mount Taranaki: a wonderfully symmetrical volcano surrounded by the equally pleasing Egmont National Park, which separates—as if compass-drawn—old-growth forest from surrounding pastures. |

|

PlanetScope • Mount Taranaki, New Zealand • March 16, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Niger River

In case you’re not sold on the impermanence of Earth’s borders, then consider that the Sahara desert used to be a lush oasis. One of the prominent relics of its former state is the Niger River. This 4,200-km (2,600 mi) river flows northeast from the tropical highlands of Guinea in West Africa. It then flows along the southern edge of the Sahara before it takes a sharp bend southward towards the ocean, creating a beautiful green thread across much of the continent. Millennia ago, the Niger River flowed directly into lakes amid the Sahara’s humid-savanna environment. But as it dried up into the desert we know today, the river’s course was rerouted and connected with another river, thus completing the bend.

|

|

Planet Visual Basemaps • The Niger River’s course along the edge of the Saharan Desert and bend southward • January 2022 |

Let’s zoom into that picture a little. The winding river is full of wonderful oddities. Deltas—wetlands formed where rivers empty their water and sediment—typically occur at its mouth, near another water source. But the Niger River has a delta in the middle of its course that’s become a thriving ecoregion. |

|

Planet Visual Basemaps • The Inner Niger Delta, Mali • January 2022 |

Borders provide opportunity, and the Niger River is no exception. It’s a vital source of water in an arid region. And it was along its banks that ancient cities—Djenné, Timbuktu, and Gao—formed, becoming powerhouses for learning and trade and witnessing the rise and fall of African empires. The Niger River’s complex history is a reminder that we inhabit spaces shaped by nature and evolve alongside it. And that with a few well-placed sand dunes, even great rivers can be rerouted. |

|

Planet Visual Basemaps • The Niger River crossing sand dunes that once blocked its flow, Mali • January 2022 |

|

|

|

Weekly Revisit

Last week we got our hands dirty and covered a scummy topic: algal blooms. They’re beautiful, sometimes dangerous, and always put on a show. So take a read and learn about how satellites spot, monitor, and study these microorganisms. Plus the whole archive can be found here if you’re extra curious.

|

|

PlanetScope • Lake Valencia, Venezuela • July 14 - August 18, 2022 |

|

|

|

|