|

|

|

|

|

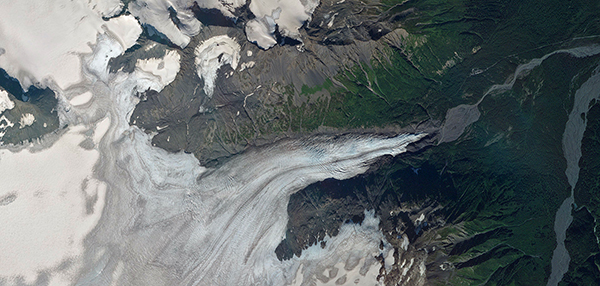

RapidEye • Exit Glacier, Alaska, USA • 2013 | In this week’s issue: Satellite constellations create long timelapses of Earth, a gigantic statue is spotted in India, and ephemeral lakes dot the Australian Outback. |

|

|

|

FEATURED STORY

Deep Timelapses

Two notable, inaugural events happened in 1957: the invention of the frisbee and the launch of the world's first satellite, Sputnik 1. While both levitate over Earth’s surface in an impressive display of physics, only one of them is responsible for pioneering the space age. And in the 60+ years since its launch, a multitude of missions have sent Earth observation satellites into orbit, revolutionizing our understanding of the planet and establishing an image archive that has vastly improved how we visualize its changes.

|  | USGS/NASA • Lake Urmia, Iran • 1997 - 2021 |

Timelapses allow us to perceive gradual planetary changes at a more accessible scale, condensing years or decades into seconds. But as its name suggests, these require time. And we’re relatively late to the game: Earth is 4.5 billion years old and estimates put the destruction of the planet somewhere between the range of 4 and 8 billion years in the future after the sun destabilizes. Meaning we’ve started taking yearbook photos around Earth’s middle age. But you’ve got to start somewhere. And given our outsized impact on the planet, we’re right in time to document some of its most formative years.

|  | RapidEye • Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia • 2011 - 2017 |

We’ve covered timelapses on Snapshots before, but this week we wanted to take a look at ones beginning relatively long ago. These sequences reach deep back in time, leveraging Earth’s historical archive to visualize the planet’s often dramatic changes. Some are made with Planet’s RapidEye constellation, which operated between 2008 and 2020. But many begin with the USGS/NASA Landsat satellites that have provided a continuous stream of publicly available remote sensing data since 1972.

|  |

USGS/NASA Landsat & PlanetScope • Matupá, Mato Grosso, Brazil • June 13, 1975 - June 13, 2021 |

The Landsat image record is a cornucopia of remote sensing data. The satellites’ spectral bands provide researchers with an array of information from surface temperature to water quality. And since they’ve been in orbit for the past 50 years, they’ve collected an unprecedented archive of historical data that’s coincided with a rapid rise in global industrialization and climate change-induced environmental degradation. Starting a timelapse with an image from Landsat’s record helps illustrate the extent of landscape transformation.

|  | USGS/NASA & PlanetScope Mosaic • Gran Chaco, Argentina • 1993 - 2022 |

Earth’s changes are vast, global, and constant. It’s difficult to visualize its wholesale evolution and even harder to mentally comprehend its scale. But timelapses break this complex story into discrete bits. They’re seconds-long stories with a direct narrative arc: segments of forest converting to agriculture, a lake shrinking due to drought, or a glacier’s terminus retreating as the climate warms.

|  | USGS/NASA Landsat & PlanetScope • Columbia Glacier, Alaska, USA • 1975 - 2021 |

Put them together, though, and these timelapses create a tapestry of change. The tech (and map-making) giant Google revolutionized the world atlas with satellite imagery when it released Google Earth in 2001, a development in cartography possibly akin to discovering that the planet is round. And their Google Earth Engine combines hundreds of data sources to create an even more precise picture of the world. The static maps of yesteryear show what a place looks like in the moment, but the maps of the future will reveal what it was like in the past too.

|  | Chuquicamata Copper Mine, Chile • 1992 - 2022 • Created by Overview • Source Imagery from Planet |

|

Our friends at Overview have been using Google Earth’s Timelapse feature paired with Landsat and Planet images to create striking visualizations of Earth’s changes over decades. They show some of the extensive impacts of resource extraction, like the above timelapse of the Chuquicamata copper mine in Chile. But also feats of human engineering—as in the construction of airports on reclaimed land—and natural wonders, like the movement of sand dunes in Brazil’s Lençóis Maranhenses National Park as coastal winds blow them inland.

|  | Lençóis Maranhenses National Park, Brazil • 1988 - 2022 • Created by Overview • Source Imagery from Planet |

The world atlas, once a tome on a coffee table, has become a digital database with searchable data points and temporal references. The visualization of the planet is made more robust by combining data sources, satellite constellations, and image repositories that allow us to index these landscapes. And as the years roll by, these changes emerge in profound detail. The archive has just begun. |

| Hong Kong International Airport • 1988 - 2022 • Created by Overview • Source Imagery from Planet |

|

|

|

Statue of Unity

Speaking of archives, we figured we’d share one of our most popular images from 2018. This oblique image shows the Statue of Unity—the world’s tallest monument—towering at 182 meters (597 feet). To put in perspective: the Statue of Liberty reaches the Statue of Unity’s knees. It was built as a tribute to the Indian statesman and independence activist Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. Though he’s nicknamed the “Iron Man of India,” his statue is covered in approximately 12,000 bronze panels. And if, like us, you rave about infographics, then check out this video comparing the sizes of the world’s largest statues.

|  | SkySat • Statue of Unity, Gujarat, India • November 15, 2018 |

|

|

|

|

What in the World: Ephemeral Lakes

Australia is chock-full of otherworldly landscapes and wildlife. We’ve seen so many intriguing images from the continent that it could fill an issue itself—and maybe it will. But before we get ahead ourselves, here’s Lake Carnegie in the Shire of Wiluna. It's an ephemeral lake, meaning it fills in the monsoon season but remains dry for much of the year.

|  | PlanetScope • Lake Carnegie, Australia • January 26, 2016 |

Just over 700 km (435 mi) away (close, by Australia’s standards) is Lake Macdonald, another ephemeral lake. In fact, scroll around the Australian Outback on Google Maps and you’ll notice them everywhere. Maybe you’ll even come across Lake Disappointment, believed to be named when an early explorer discovered it was a salt lake, not freshwater. We personally don’t think a lake has to be fresh to be great, and we find their ephemeral patterns to be pretty special. But who really wants to judge a lake anyway?

|  | PlanetScope • Lake Macdonald, Australia • March 24, 2016 |

|

|

|

|

|