|

|

|

|

|

PlanetScope • Kirkuk, Iraq • June 18, 2019 |

In this week’s issue: We interview Wim Zwijnenburg about his work monitoring environmental damages resulting from war, summer solstice is reached in the Northern Hemisphere, and a strip of midnight sun is captured in the Lena River Delta. |

|

|

|

FEATURED STORY

The Environmental Cost of War

There’s no reasonable way to tally the cost of a war. When we try to measure its casualties, we naturally gravitate towards the numbers of lives lost and people displaced. But wars aren’t fought in isolation. Its battlefield is the environment. And after the firing stops, the smoke clears, and strategic footholds established, the damage is far from complete. It lingers in the Earth and continues to harm those that depend on it for decades after.

It’s understandable to overlook the environmental cost of war amid human suffering. But it’s also vital to keep track of this quieter form of violence simultaneously taking place. Whether it’s directly weaponized, as in targeted attacks on water infrastructure, or wounded in the crossfire, like wildfires and toxic pollution, its damage often goes unseen. But in recent years, a growing group of organizations, experts, and researchers are turning to open-source intelligence (OSINT) to monitor this destruction, help those affected, and hold its perpetrators accountable.

|  |

A video showing a column of yellow smoke rising from an alleged Russian drone strike was shared on social media. PAX used Planet imagery to confirm it was likely storage of ammonium-nitrate in Dolgenkoye, Ukraine. Source imagery by Planet • Analytics by PAX |

This week, we followed-up with Wim Zwijnenburg about his work monitoring environmental hazards born from war. Wim is a Humanitarian Disarmament Project Leader for the Dutch peace organization PAX and a contributor to Bellingcat, an OSINT investigative journalism group. His work focuses on emerging military technologies and their impact on how wars are being fought and consequences for arms proliferation.

* This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

|  |

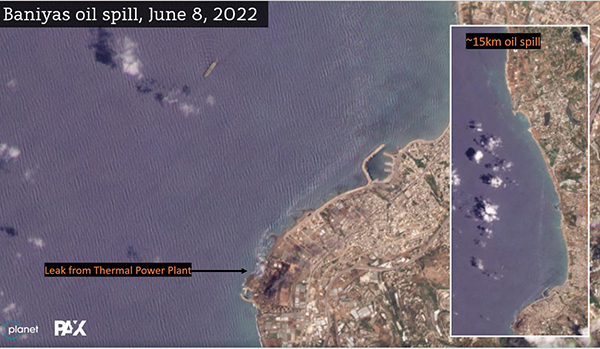

An oil spill kilometers-long is seen in the ocean on the coast of Syria after a leak at the Baniyas Thermal Power Plant. Source imagery by Planet • Analytics by PAX |

Before the proliferation of publicly-available satellite data, how would OSINT investigators go about finding, tracking, and sharing environmental damage caused by war?

The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) was doing post-conflict environmental assessments, starting off in conflicts such as the Balkan Wars, Iraq, and Sudan. Basically what they did is they got a mandate to do an assessment, but the scope of their work was limited as social media and other open-source information was not widely available back then. Traditional OSINT in the pre-social media era was mainly driven by access to information from public media and commercial satellite imagery. Intelligence agencies often just went to newspaper articles to collect information on events in areas of interest. From an environmental perspective, research was mainly driven by field work from organizations such as Greenpeace or by local NGOs, but the latter often had limited exposure on an international level.

The OSINT that we know nowadays started off with the Syria conflict. Syria, until Ukraine, was considered the most documented conflict in the world. There was actually more recorded war footage from Syria than the time that existed since the war started. Meaning there was more than 10 years of filmed data of the conflict because there were so many videos being uploaded and shared. And that’s where OSINT investigations as we recognize today were founded. Using social media footage, Google Earth, and other satellite imagery, investigators and activists were able to monitor weapons use through geo-location and documenting human rights violations.

|

|

Oil waste is seen covering soil near Tall Mashhan, Syria after a river was flooded. PlanetScope • November 25 - December 15, 2018 |

Are there different environmental risks associated with a conflict’s location? What are some of the recurring/common damages you’ve come across in your research?

Every conflict has its own unique environmental footprint. In Syria, we saw a lot of oil pollution in the east, caused by bombed refinineries and makeshift oil refining, and lack of enforcement and regulation resulting in the dumping of waste to rivers and creeks. In Iraq, there was water infrastructure damage and oil well fires. Ukraine is unique in that it's a very industrialized country—particularly in the eastern Donbas region—with a lot of coal mining extraction, chemical factories, abandoned mines filled with toxic waste, and agricultural facilities storing hazardous substances.

Depending on the environmental, geological, or industrial conditions, and the type of economy being run, you have very specific environmental dimensions to each conflict. So it depends what kind of natural resources and wider environmental conditions there are and how it's being affected. But there are a couple of things that are always recurring, which are closely linked with people’s health. The first is damage to critical infrastructure—you see that in every conflict, and it's something you can help identify by looking at damage to pumping stations, damage to water facilities, sewage treatment plants, and power stations. This directly impacts access to clean water or results in shutdown of essential services for civilians.

There’s also damage to urban areas from intense fighting, which pose direct risk to civilians living there but also creates millions of tons of conflict rubble: collapsed houses and buildings which are often mixed with substances such as asbestos, heavy metals, and industrial, household, and medical waste. The third issue is the collapse of environmental governance, in particular highly industrialized societies. During peacetime these areas have regulated industrial facilities and waste disposal systems. But in conflicts that sort of disappears, and can sometimes result in outbreaks of communicable diseases like cholera, which we see now in Mariupol because people don’t have access to clean water.

|

|

The village of Kharab Abu Ghalib, Syria is flooded by oil. PlanetScope • March 9 - 23, 2020 |

How long do you continue to monitor and assess an area after a conflict ends?

It sort of depends. We can scale down our work after a certain period once other governments and NGOs step in. But in Syria there’s no one else looking at the environmental damage in a sustained way, so we continue to monitor there. As long as there’s no one else, the urgency remains, and we have the funding, we’ll continue doing this. Yet obtaining funding is often problematic, as environmental issues are traditionally not prioritized in conflict, often for understandable reasons. But the need to properly monitor these impacts is growing. It’s crucial that conflict-linked environmental degradation is effectively addressed in the reconstruction phase.

Our initial monitoring work in Iraq helped raise the profile of the environmental damage there and also helped push for a UN resolution in the UN Environment Assembly in 2017. And as a result of that resolution, funding became available for UNEP to do an assessment of environmental damage and cleanup of oil pollution, debris in cities, and reparation of water infrastructure. It kick-started a process that’s then been taken over by development organizations. We do research-based advocacy so that others can do the on-the-ground work.

|

|

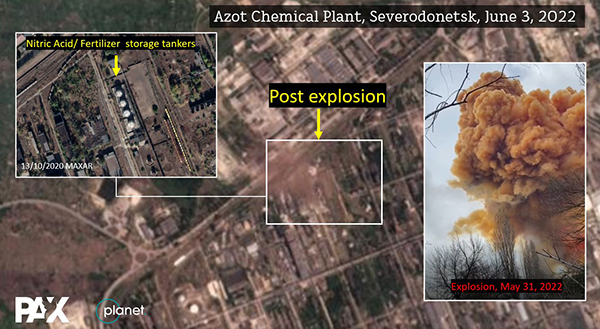

Four tankers allegedly storing nitric-acid exploded after Russian shelling, sending a toxic plume of smoke into the air and threatening civilian health in Severodonetsk, Ukraine. Source imagery by Planet • Analytics by PAX |

Are there certain environmental damages invisible to on-the-ground sources but are observable to satellites?

It depends on how you define invisible. There’s the spatial-temporal value of satellite imagery—you can show if there's a change in vegetation growth, deforestation, or water levels over time. These are visible to eyes on the ground if you go there every day, but it’s easier with satellites. Air pollution, land temperature and other sensor information are not directly visible with the naked eye but can be picked up by satellites, which is helpful in the research, e.g. using near-infrared imagery.

The other answer is access. Because of security reasons researchers can’t go to certain places to see what’s going on. But with satellite imagery we’re able to verify claims or falsify statements to see what’s happening there. Think of conflict areas, but also oil spills in the sea that can be detected with satellites. If you define invisible as not being able to be seen, then satellites are an important instrument in the OSINT toolkit.

|

|

A strike destroys Mikolayiv’s Nika-Tera grain storage sites as part of Russia’s campaign to target Ukraine’s food supplies and agricultural facilities. SkySat • May 31 - June 7, 2022 |

|

How does environmental damage caused by war interact with stresses already exacerbated by climate change?

Conflicts result in degraded government systems that are there to protect the environment: forestry, water use, or agricultural practices. When this is affected by a conflict, climate change-related stresses such as droughts or extreme weather events will only compound these impacts and exacerbate the environmental problems. Let me give you two examples:

In the spring and summer of 2018, we saw massive fires in all of Syria and Iraq. In the winter there was heavy rain followed by a very early heat wave in springtime. Which means the crops started to grow fast, but also dense growth of wheat among the weeds. But because of the heat wave, the smaller wheat started to dry very fast. So every time there was a small spark, or cigarette butt, but also conflict-linked causes such as artillery fire, or intentional torching, it spread very fast because there was so much dry vegetation. So there were massive fires that burned down all these crops. But there was not an effective firefighter force able to combat the fires, or they were at risk from unexploded ordnance or boobytraps hidden in the crop fields.

Another is in Syria, where there is massive deforestation driven by the need for firewood. Already 25% of all Syria’s forests have been cut during the conflict. Yet trees are both natural carbon sinks and have a cooling effect, so losing much forest is posing additional problems for Syria in dealing with growing climate impacts. |

|

A cropland burns after being torched by the so-called Islamic State in Sulaimaniya, Iraq. A PAX investigation found the fires to be “driving people from their houses, destroying orchards and posing risks to firefighters as the area is heavily contaminated with landmines and unexploded ordnance.” PlanetScope • August 3, 2020 |

What’s the next step for progressing innovative OSINT technologies? And how can this monitoring be better turned into actionable policy?

At the beginning of modern-day OSINT investigations in 2012, Facebook and Twitter were driving data collection. Then it switched to Instagram. And now in Ukraine you see a lot of Telegram and TikTok. Every time there’s a new app with new information sharing possibilities, you see more open-source opportunities. That will likely continue to change.

At a professional level, we’re seeing more optical sensors and higher-resolution data being made publicly available. We’ll probably see more applications of machine learning and AI in remote sensing that is helping quickly identify changes in the environment or damage assessments. Being able to deal with large quantities of data through accessible platforms will make a change in terms of open-source information.

|

|

The FSO Safer leaks oil into the Red Sea near Yemen. SkySat • September 14, 2020 |

You can read more of Wim’s articles here and find his Twitter here. |

|

|

|

Summer Solstice: Minihenge

Summer solstice occurred in the Northern Hemisphere this Tuesday. It happens when the Earth reaches maximum tilt towards the sun, creating the longest period of daylight in the yearly calendar and kicking off the official start to summer. While some brands celebrate with a call to “find your beach,” we prefer finding ancient rings of large stones aligned with the sun’s solstices. England’s legendary Stonehenge was built sometime between 3000 and 1520 BCE, but not much else is known about the structure’s purpose. Its intentional configuration, however, lends itself to a pretty mesmerizing view on summer solstice day.

|  | SkySat • Stonehenge, Amesbury, England • April 15, 2022 |

Okay fine, we like beaches too. So here’s a beautiful stretch of coastline along Garden Island off the coast of Western Australia. |  |

SkySat • Garden Island, Australia • July 10, 2020 |

|

|

|

|

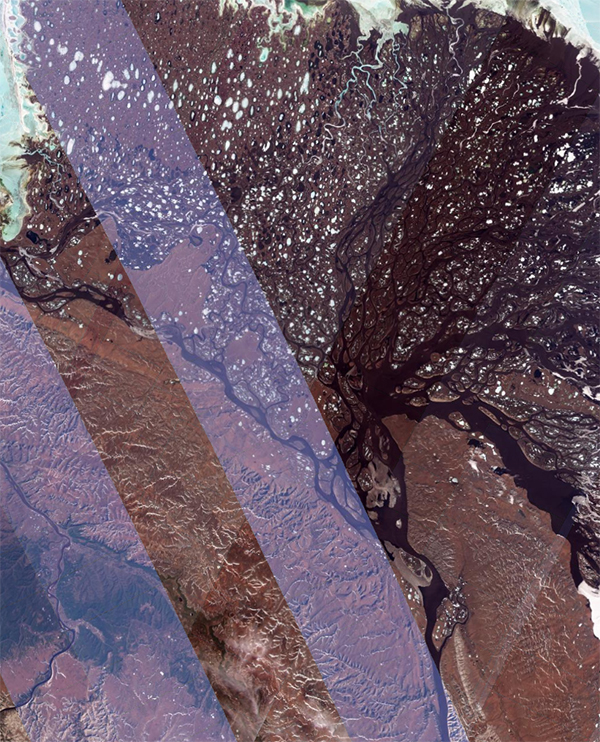

Satellite Explainer: Midnight Sun

While searching through our recent imagery for the Lena River Delta we shared in last week’s issue, we came across an unusual strip of bright blue data. The reason? Around this time of year, latitudes north of the Arctic Circle experience what’s called the “midnight sun,” which is when the sun stays above the horizon 24 hours a day. Our Doves only take an image when there is enough light to clearly see Earth’s surface. Meaning they don’t usually capture images at night. But along the Siberian coast around this time of year, there is no night, only midnight sun. So as this satellite orbited over the delta during the “night,” it captured a series of images resulting in a strip of Arctic midnight blue.

|  | Screenshot of unprocessed PlanetScope • Lena River Delta, Siberia, Russia • June 11, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

|