|

|

|

|

|

PlanetScope • Navajo Lake, New Mexico, USA • August 15, 2021 |

In this week’s issue: Satellites monitor drought across the world, an otherworldly partially-frozen delta is spotted in Siberia, a glacier collapses on the northern flank of an inactive volcano in Ecuador, and an airport is built on an artificial island in South Korea. |

|

|

|

FEATURED STORY

Drought

Climate change is a fickle problem. Its timescale is hard to grasp: eons for the planet, generations for us—an encroaching tempest on the horizon. But it wields the weather as its weapon, lashing out in explicit strikes. And as it approaches, more of the sunny skies and temperate conditions we’ve become accustomed to are clouded by storm clouds, the first strikes of lightning, and a spitting rain.

But its advance is sinister: flooding one place while drying the area next to it. Among the many steadfast ecological pillars we’re losing because of climate change, regularity and predictability are perhaps most prominent. It’s why, as you read this, Yellowstone National Park reels from a deluge of rain while wildfires rage in Arizona and a megadrought grips much of the American West in a dry, unforgiving chokehold.

|  | PlanetScope • Lake Mead, Nevada & Arizona, USA • June 12, 2021 |

This week, we’re turning our attention to the global epidemic of drought—a prolonged period of below-normal precipitation and decreased soil moisture across an area of land. Drought is a natural part of Earth’s climate variations. But climate change is making it more frequent, more severe, and longer-lasting. It’s both an indicator of environmental anomalies and a stressor for the ecosystems that rely on stable precipitation patterns. Drought, in that case, is both the thermometer and the virus. The delivered sentence and the executioner.

|  | PlanetScope • Portland, Oregon, USA • September 9, 2020 |

Unlike gas prices, drought’s global fluctuations aren’t marked at 3-mile intervals on rising incandescent gas station numbers (though perhaps they should be). Instead, they’re measured in meteorological trends, snowpack levels, and bumper stickers with the clarion call to “conserve water.” Like tumbleweeds rolling across a parched, cracked desert, these signs portend an unforgiving summer season, and a darker, drier outlook for the years ahead.

|  | PlanetScope • Sacramento River Valley, California, USA • May 31, 2021 - 2022 |

Like the edges of a desert, there is no distinct beginning or ending to a period of drought; it proceeds and recedes gradually. It’s only after weeks, or even years, of low rainfall, reduced soil moisture, and falling reservoir levels is a drought officially declared. This is one of the greatest cognitive barriers to conceptualizing drought. Unlike floods, wildfires, and heat waves, drought’s effects aren’t immediately acute. It’s an environmental state more aligned with changes like sea level rise and greenhouse gas emissions—a seemingly invisible form of damage belonging to a category termed “slow violence.”

|  | PlanetScope • Lake Powell, Utah, USA • May 20, 2021 - April 21, 2022 |

An effective tool for visualizing slow violence is to work on the time frame over which it takes place. Stare at the sun (don’t actually do this) and you won’t see it move, but go about your day and Earth’s rotation will manifest through the changing light. From space, drought is best captured at the scale of years. Utah’s Great Salt Lake has shrunk by two thirds due to a drying climate and a rising human population in the area. Take two pictures of it a day apart and you won’t see a change. But compare an image today from one taken 34 years ago and its trend takes form.

|  | Landsat & PlanetScope • Great Salt Lake, Utah, USA • 1987 - 2021 |

Shrinking reservoirs and wildfires are two of the most common aerial illustrations of drought. The message they send is clear, accessible, and striking. But drought is truly measured by data. Precipitation patterns, amount of snowpack, and other indices are combined to calculate the extent of an area’s water resources. And satellites provide a powerful supplemental dataset to this measurement. The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) estimates plant health over time by comparing whether an area has gotten greener or browner. That’s a simplification, but it produces a picture of how drought affects vegetative health over large regions.

|  | NDVI comparison of the Russian River Watershed in California during the same two week period in 2020 and 2021 |

|

Drought is one facet of climate change. And like climate change, its causes are multitudinous and its damage extensive. It’s a bad situation, no drought about it. But it’s by no means unsolvable. At the macro level, wholesale intervention is needed: everything from greenhouse gas reduction to more efficient water management. But local solutions have an impact too. And some are already yielding results that can be seen from space.

|  | SkySat • Hoover Dam, Nevada, USA • December 12, 2018 |

Justdiggit is a literal grassroots movement on a mission to help cool the planet by regreening Africa and restoring climate change-induced desiccated land. Their tools? Shovels. They dig semi-circular pits called bunds that help the soil capture and retain rainwater instead of it washing away on the harder upper layer of cracked dirt. Better water retention means more fertile soil, regrowth of vegetation, and improved livelihoods for the communities that depend on a healthy Earth. In Pembamato Tanzania, the organization dug bunds on two plots of arid land in 2018. Four years later the plots emerge from the bone dry soil in verdant green.

|  | PlanetScope • Pembamato, Tanzania • May 27, 2018 - May 11, 2022 |

Local solutions won’t solve drought-related stresses alone, but neither will proposed macro solutions—at least not in the timeframe needed to avoid the worst of climate disaster. A coalition of many is needed to enact positive change. And in-the-air data paired with on-the-ground actions can help keep the tempest at bay. |

| PlanetScope • Tule Lake, California, USA • May 26, 2021 - May 20, 2022 |

|

|

|

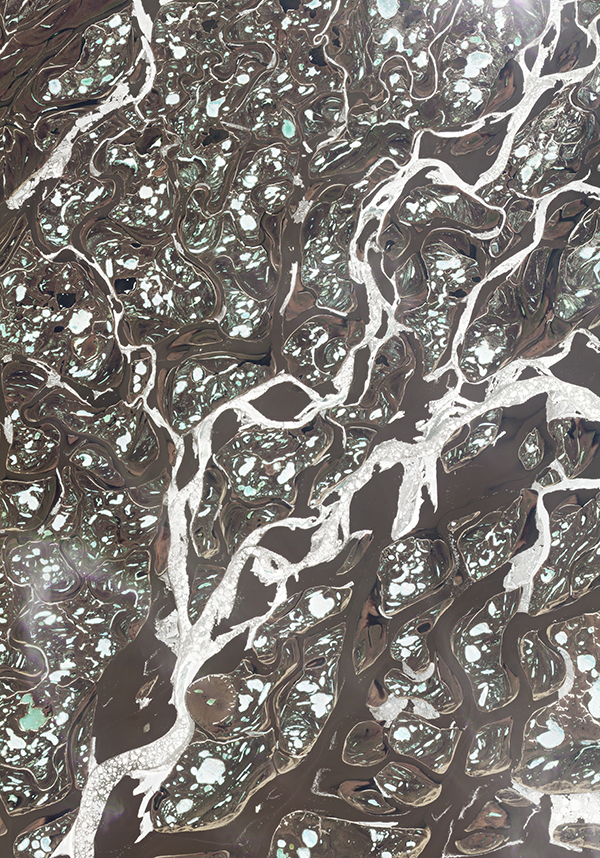

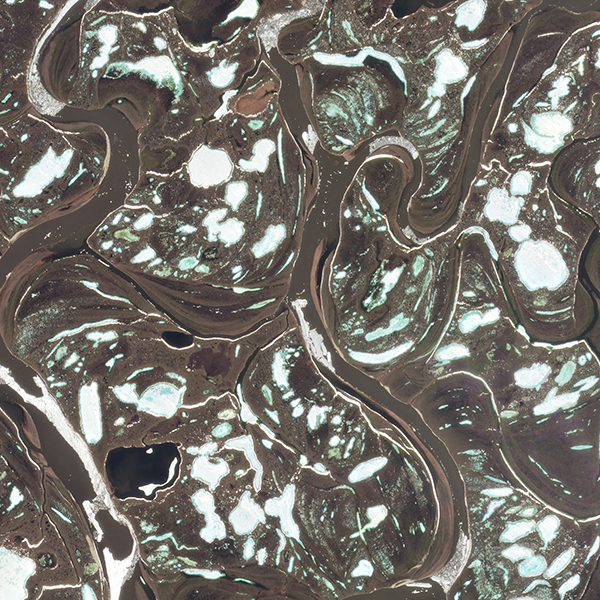

What in the World: Lena River Delta

Welcome to ‘What in the World,’ a section where we take a look at some otherworldly sights we’ve captured from pole to pole. For one reason or another we find these scenes to stand out. So we’re kicking things off with a location that looks like something we imagine to be found on the diamond planet of 55 Cancri e.

|  | PlanetScope • Lena River Delta, Siberia, Russia • June 6, 2022 |

On Earth, though, we just call this a partially frozen delta, one that covers an area of tundra larger than the state of Maryland. This is the end of the Lena River as it winds north towards the Arctic Ocean before emptying into the Laptev Sea. Around 30,000 small lakes form as the permafrost thaws in Spring, though most are still seen frozen in this early June image. Ice, moss, shrubs, mudflats, sand beaches, and sediment-filled streams create this sparkling tapestry, gem-like in its radiance.

|  | PlanetScope • Lena River Delta, Siberia, Russia • June 6, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

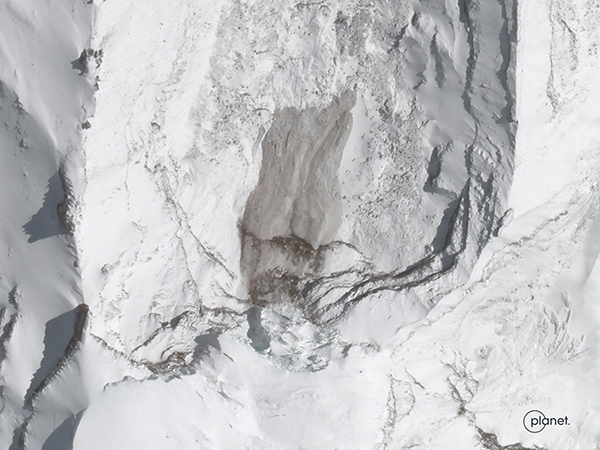

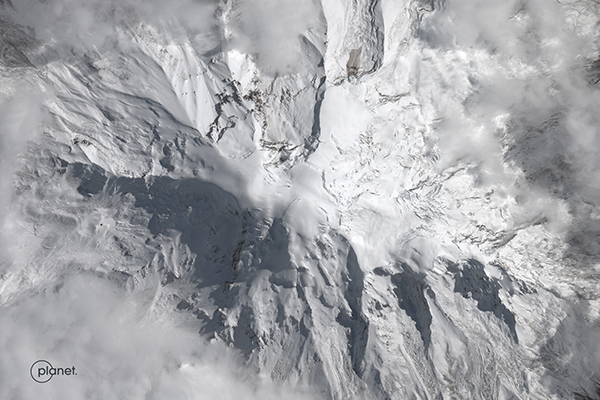

Change of the Week: Glacial Collapse

If a glacier collapses at the top of an inactive volcano and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? It probably does. But honestly, we don’t know much else about this event that took place on the northern flank of Ecuador’s Chimborazo mountain. Robert Simmon, a Senior Data Visualization Engineer at Planet, spotted a change in the landscape between June 7th and 8th, but we haven’t determined anything else besides what’s shown here. Have an idea of what happened? Let us know!

|  | SkySat • Chimborazo, Ecuador • June 8, 2022 |

Interestingly, Chimborazo’s summit is the farthest location on Earth’s surface from its core, despite being only the 39th tallest mountain in the Andes alone. The Earth is actually shaped as an oblate spheroid (far less catchy than “sphere”), so the distance from core to equator is about 21 km (13 mi) greater than to the poles. Chimborazo sits right on this ellipsoidal bulge, pushing its core-to-surface distance to over 2,000 meters (6,500 feet) farther than Mount Everest.

|  | SkySat • Chimborazo, Ecuador • June 8, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

Instagram Highlight: Daily Overview

They say Rome wasn’t built in a day. Apparently, neither was South Korea’s Incheon International Airport. This week, Overview created a timelapse of the airport’s construction on reclaimed land between two islands 30 miles west of Seoul. Take a look as the artificial island grows between 1984 and 2022.

|  | Created by Overview • Source imagery by Planet and Landsat |

|

|

|

|