|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PlanetScope • North Caucasus, Russia • June 27, 2016 |

| In this week’s issue: How satellite data is helping shape the next agricultural revolution, Russia targets grain supply in Ukraine, a ring dike protects a community from flood in Canada, and a glacier lake outburst flood wipes out a bridge in Pakistan.

|

|

|

|

|

FEATURED STORY Agriculture |

| Agriculture is the fertile soil on which civilization grows. As humans have expanded across the globe, so too has the area we’ve dedicated to farming, grazing, and growing. Agricultural land covers 38% of Earth’s total land surface, or about half of all habitable land. If you’ve ever flown long distance or scrolled around a mapping app, you’ve likely noticed that cities appear like microscopic nodes amid seemingly endless fields. Over the past 12,000 years, we’ve rapidly cleared and partitioned the land into neat, designated parcels for commodity cultivation. But time and time again our lofty ambitions have run into the wall of finite returns. |

|

| PlanetScope • Toshka, Egypt • May 12, 2016 |

| The central agricultural problem has long been how to produce more from the same size of land. More food is needed to accommodate rising populations and shifting diets, but the amount of land on Earth remains the same. In the 20th century, we overcame food insecurity crises through the application of revolutionary technologies: nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides, and high-yielding crop varieties. Today, global food insecurity is largely driven by political instability and climate change. The next revolution will need to accomplish the task of producing more from less as well insulating itself from increasingly volatile climates. And this revolution won’t be driven by nitrogen, but by data. |

|

| PlanetScope • North Platte, Nebraska, USA • April - October, 2019 |

| We’ve somehow gone 25 issues without discussing the big green agricultural elephant in the room. It’s an in-depth subject that’s as fascinating as it can be complicated. So for now we’re just dipping our toes in the irrigated water. Satellites are usually a good match for anything that happens over vast areas. And as we mentioned before, 38%—or 5 billion hectares (12.4 billion acres)—of Earth’s surface is used for agriculture. That’s far too large for landowners to monitor on their own. But satellites extend our eyesight and reveal insights otherwise unknown. |

|

| PlanetScope • Central Pivot Irrigation, Saudi Arabia • April 18, 2016 |

| At its simplest level, satellite data helps direct farmers to locate where there are problems on their land. Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of orange juice, and, as you might imagine, they dedicate a lot of land to growing citrus trees—about the size of Rhode Island. In order to monitor these vast stretches of land for weeds, pests, disease, and nutrient stress, Brazilian agronomists turn to aerial imagery. Like nitrogen, satellite data is an input that can boost yields and save farmers money. |

|

| PlanetScope • São Paulo, Brazil • September 27, 2020 - February 7, 2021 |

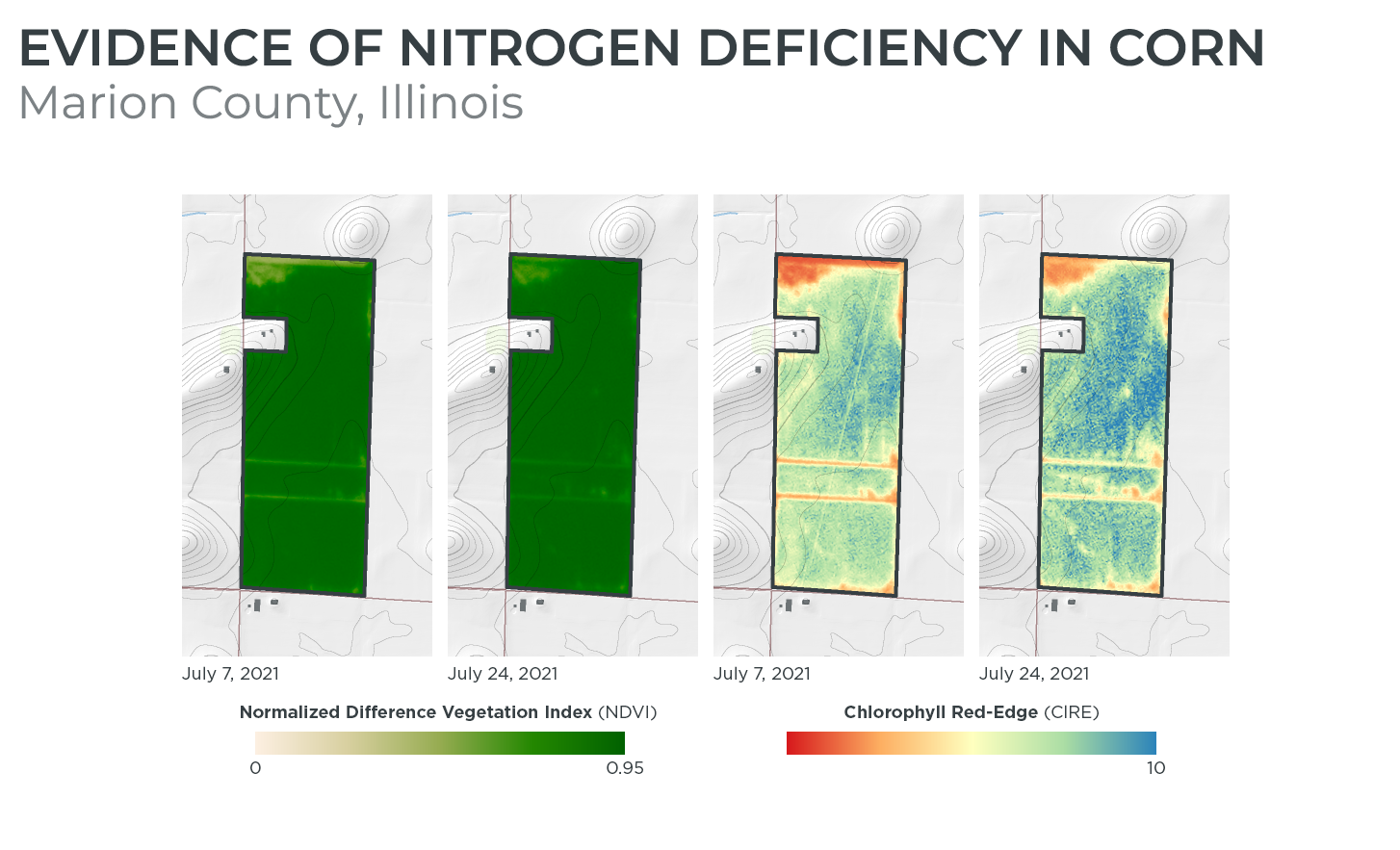

| If you have one image of an area on Earth, you can show a place in time. With multiple images you can show how it changes over time. And if you add layers and indices on top of these, you can begin to create a more dynamic representation that is more informative than the visual image alone. They can measure data like soil water content, land surface temperature, and crop biomass. Indices like NDRE (normalized difference red edge index) and CIRE (chlorophyll index - red-edge) quantify patterns that the RGB (red-green-blue color model, or true color) images simply miss, like the relative density and health of crops. |

|

| PlanetScope • Marion County, IL • July 7, 2021 |

| Take something like the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI). Satellites capture light wave information over scanned areas, and algorithms can convert that raw data into an index. NDVI shows how healthy a plant is based on the amount of light it reflects. It’s essentially a measure of an area’s greenness. It’s a simple index but it’s an effective method for calculating agricultural yield and discerning a general impression of vegetative health. Like a needle in a haystack, the NDVI—and the other indices—allow farmers to spot those small trends that indicate something is either going wrong or right. |

|

| PlanetScope • Boulogne-sur-Gesse, France • April - November, 2020 |

|

| In recent years, nitrogen fertilizer prices have skyrocketed as natural gas increases in cost and political instability disrupts supply chains. This has pushed food prices up nearly 30% and further stressed the demand for technologies to help stabilize the situation. Satellite data is just one of many inputs needed to optimize production and help food insecurity, but it’s a valuable one. The red-edge spectral band is particularly good at calculating nitrogen concentration in crops. When used effectively, satellite data can pinpoint which fields are performing as expected and which aren’t. Instead of evenly distributing fertilizer, farmers can then allocate a greater share to the more productive fields, limiting cost and maximizing crop growth. |

|

| NDVI and CIRE comparison |

| In its most elementary form, agriculture is the practice of converting inputs into outputs on a finite surface. The more ways we discover how to sustainably produce more using less resources and land, the better off we’ll be. The demand on agriculture production is only going to intensify in the coming decades as global populations grow. But we can ensure that it also gets more precise, optimal, and equitable. It’s just a matter of selecting the right inputs. |

|

| PlanetScope • Chavimochic Special Project, Peru • March 26, 2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ring Dike |

| Here’s a tip: before the waters rise, raise a ring dike. That’s a lesson the small Canadian town of Morris knows all too well. The Red River Valley area is so prone to seasonal floods that 18 ring dikes were constructed to protect its communities from flood damage. How effective are they? Well take a look at the false-color image below. Red shows where vegetation is, and the turquoise shades denote the presence of water. Though the fields are seen inundated with floodwater, Morris and its ring dike emerge from the diluvial plain like an ark after a biblical storm. |

|

| PlanetScope • Morris, Manitoba, Canada • May 7, 2022

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|