|

|

|

PlanetScope • Keep River Inlet, Australia • March 15, 2015

|

|

In this week’s issue: Satellites spot fractal patterns across the Earth, an oil depot near a F1 circuit is attacked in Saudi Arabia, shallow shelves appear in the Red Sea, and an inland delta

swells with water in Botswana.

|

|

|

|

|

FEATURED STORY

Natural Fractals

|

|

What do lightning strikes, mountain ranges, and Romanesco broccoli have in common? Besides a flair for the dramatic, they all demonstrate fractal properties.

A fractal is a geometric figure that is self-similar across different scales and is infinitely complex.

Also infinitely complex—at least for us non-mathematicians—is trying to read any online entry about fractal mathematics.

They even have their own dimension, but we’re not going to get into that today (or ever).

|

|

|

PlanetScope • Derby, Australia • February 14, 2022

|

|

For most of us, fractals are best known for their self-similarity: how each small part of its shape acts as a copy of the whole.

This pattern repeats at many scales.

In theoretical mathematics, the pattern makes perfect smaller copies of itself forever.

But in the natural world it usually only repeats a few times.

And since Earth isn’t theoretical, the copies aren’t perfect, but they’re close.

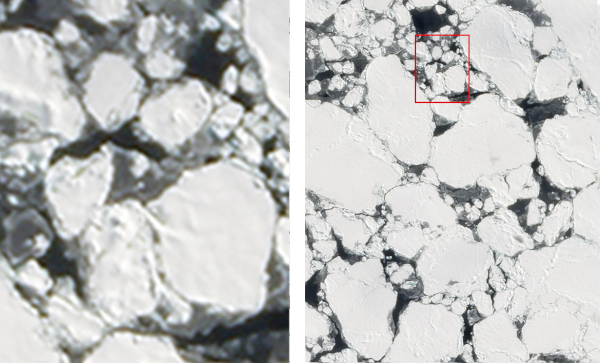

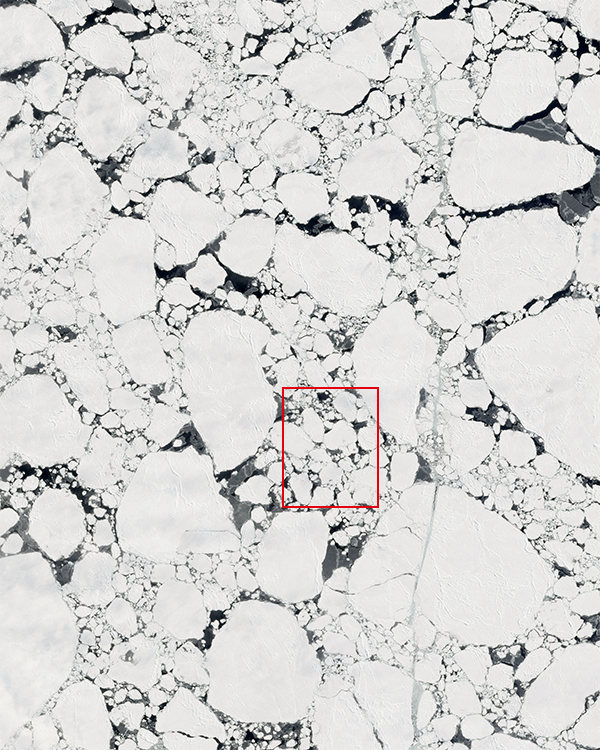

Take a look as we zoom into these chunks of ice floating in the Antarctic sea.

The first image is a zoomed in version of the image to its right.

And that image is zoomed in section from the one below.

Yet despite the magnification, the structure looks similar across all scales.

|

|

|

|

SkySat • Antarctica • February 20, 2022

|

|

Maybe you’ve seen those trippy gifs of a perpetually-zooming camera falling deep into a fractal design (if not, strap in and click this Giphy link).

Usually zooming in will show you a new detail within an image, and it’ll look overall different than before.

But with fractals, zooming in essentially changes nothing.

The pattern remains the same.

The zoom in is the same as the zoom out.

The multiple arms of Baffin Bay inlet in Texas demonstrate this effect quite well.

The first image is about 30 miles (48 km) wide.

The last, most zoomed in image, is about 2 miles (3 km).

But the overall structure remains similar.

|

|

|

Fractals are often explained through natural objects, where the pattern can be more tangibly understood, like tree branches, ferns, and snowflakes.

All of these take their design and repeat it multiple times at smaller scales.

But fractal patterns are far more ingrained in our natural world.

They’re present from DNA to galaxies and all over in between.

And when you look at enough satellite imagery they start popping up everywhere too.

|

|

|

SkySat • Burrup, Australia • November 21, 2020

|

|

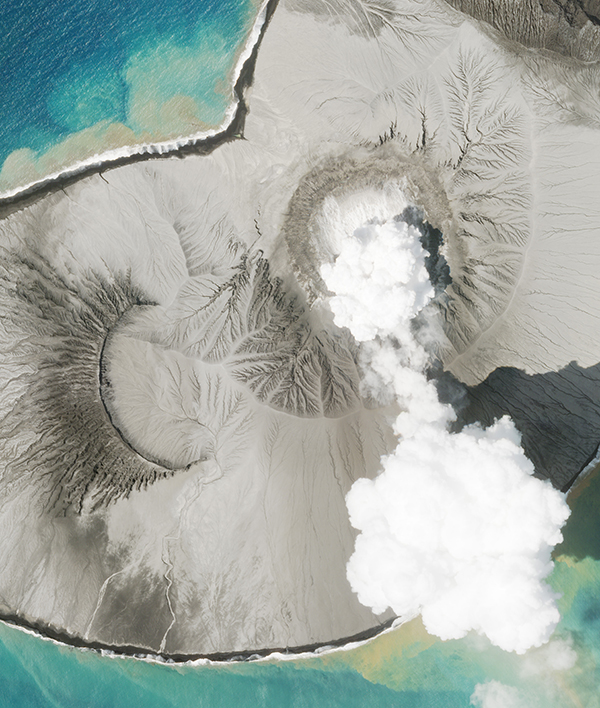

Mountain ranges, frozen seas, deltas, clouds, coastlines, and canyons.

Fractal patterns are embedded in the structures of Earth visible to satellites.

We expect to notice them regularly among certain formations like rivers, but they also tend to emerge in surprising places.

Remember the volcanic eruption in Tonga from February? Well we spotted fractals there too.

|

|

|

SkySat • Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai, Tonga • January 7, 2022

|

|

Usually fractal patterns jump out of Earth images like a crack of lightning.

But sometimes it takes an extra spark for them to be revealed.

In the Australian Outback, a wildfire took on a branching, lung-like shape as it progressed through drainage channels filled with fuel.

|

|

|

PlanetScope • Cooya Pooya, Australia • October 30 - November 13, 2021

|

|

|

The word “fractal” was coined in the 1970s and comes from the Latin word for “broken.” The term is meant to describe how the neat world of classical geometry is unequipped to measure or describe the irregular and fragmented spaces we inhabit on this planet.

|

|

|

PlanetScope • Broome, Australia • December 15, 2021

|

|

Whether you’re using a microscope to study the small, a telescope to gaze upon the cosmos, or a satellite to view our Earth, keep an eye out for fractal patterns.

They’ll be there.

|

|

|

RapidEye • Waterton Lakes National Park, Canada • August 27, 2019

|

|

|

|

North Jeddah Bulk Plant

|

|

An oil depot destroyed by rockets and rubber burned on a newly-built Formula 1 track: two disparate scenes that took place just 11 km (7 mi) apart in the city of Jeddah last Friday.

Yemen’s Houthi rebels attacked the Saudi Arabian oil plant as the war between the insurgents and a Saudi-led coalition approaches its 7th anniversary.

Images on the night of the attack show roaring fires spewing from the oil depot.

And satellite imagery from the day after shows black smoke billowing from the wreckage.

|

|

|

SkySat • North Jeddah Bulk Plant, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia • March 26, 2022

|

|

After the attack, Formula 1 officials and drivers held emergency meetings to discuss whether the Grand Prix event at the Jeddah Corniche Circuit would continue (it did).

Popular international sports like F1 and football (soccer) are navigating the trickiness of hosting events in countries engaged in

geopolitical conflicts or other scrutiny.

|

|

|

SkySat • Jeddah Corniche Circuit, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia • November 21, 2021

|

|

|

|

Sea Shelves by the Sea Shore

|

|

Here’s a tongue twister for you: sandy land meets salty sea on Shalateen’s shores.

The town is located on the Red Sea’s coast in the Hala’ib Triangle, a contested region claimed by both Egypt and Sudan.

The atypical formations seen in the not-so-red-but-actually-very-blue sea are shallow shelves formed by the water’s high salt concentration.

The Red Sea is the most northern tropical ocean in the world.

But the “Red” in its name might actually refer to its southern position, similar to how the Black Sea is thought to be named after the north.

Either that or the presence of cyanobacteria that turn the water red.

We’ll let you choose whichever reason you prefer.

|

|

|

PlanetScope • Shalateen, Hala'ib Triangle • February 23, 2022

|

|

|

|

Okavango Delta

|

|

If life imitates art, then Botswana’s Okavango Delta takes after the abstract expressionists.

Instead of flowing into a sea or ocean, this inland delta culminates in a system of marshlands, wetlands, and plains.

During the height of the dry season rainwater floods the delta, doubling its size and making it an ecological paradise for hundreds of

different species.

Take a look as it cycles through the months between October 2021 and February 2022.

|

|

|

Basemaps • Okavango Delta, Botswana • October 2021 - February 2022

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|