|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

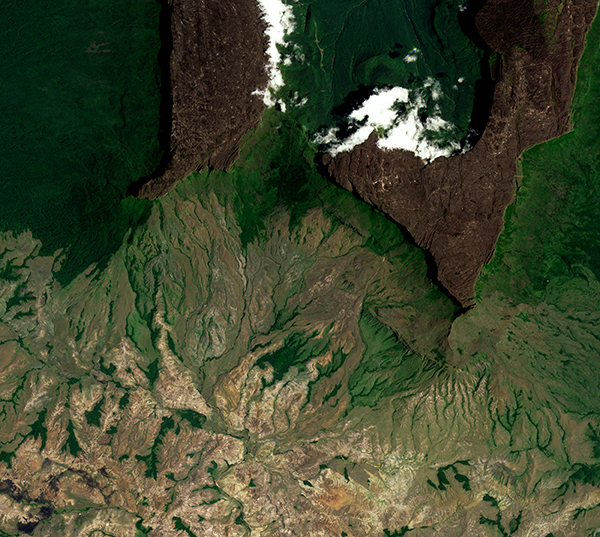

PlanetScope • Manu Biosphere Reserve, Peru • June 21, 2023 |

In this week’s issue:

Having trouble viewing images? Then read this issue on Medium! |

|

|

|

|

FEATURE STORYBiodiversity

Things tend to meld together when looking at Earth from orbit. Like a camera out of focus, the lines between different areas can be hard to distinguish. Step too far back and only the impressions of ecosystems—wet and dry, barren and lush—can be seen. Zoom all the way in and you’ll find the genetic and biological building blocks that create Earth’s living organisms. But get too close and you risk missing the whole picture. And, at least in our view, it’s the living web between big and small that makes the picture worth viewing.

Biodiversity is the variety of life found on Earth, from microbes to blue whales. Put it all together and the picture created is both beautiful and complicated—in no small part because us humans are included in it. To put it lightly, global biodiversity is in peril. So many species are dying that a growing number of experts consider us living within the sixth mass extinction. It’s a bio-recession. But unlike the market, there’s a very visible hand shepherding the annihilation: as other species die, ours thrives.

|

|

|

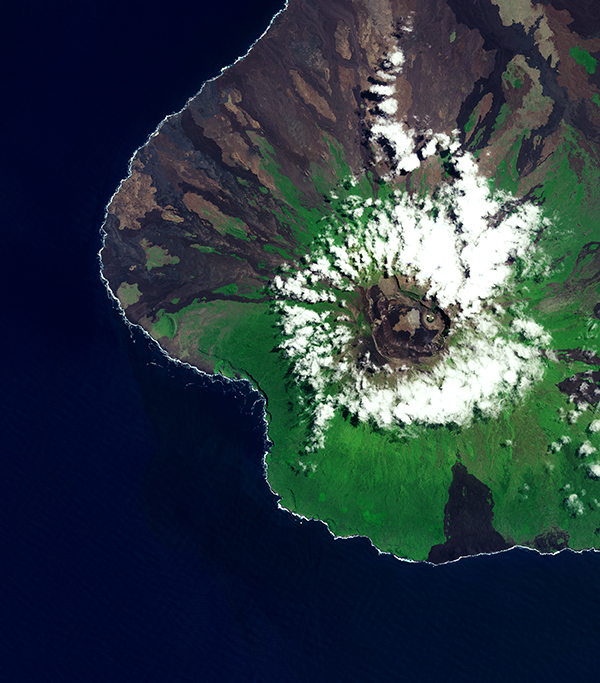

PlanetScope • Isabela Island, Galápagos Islands, Ecuador • April 27, 2022 |

If the pivotal literary work of the 19th century was Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, its 21st century edition would likely replace “Origin” with “Decline.” Somewhere around one million plant and animal species are now at risk of extinction, threatened by loss of habitat from direct human activity (logging, agriculture, urbanization) and landscapes altered by climate change. |

|

|

PlanetScope • Deforestation near Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia • April 21, 2023 |

So far we’ve identified nearly 2 million species, but higher estimates are at millions more. Scientists discover around 18,000 new ones a year. Yet at the same time, reports place current extinctions at 100 times the natural background rate—an amount that’s accelerating. Meaning it’s possible that species are going extinct faster than we can discover them. You usually don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone, but in this case, we don’t know what we’ve got and it’s gone. |

|

|

SkySat • Wai’anae Range, O’ahu, Hawaii, USA • April 3, 2022 |

Part of the difficulty with protecting biodiversity is that we still know relatively little. And predicting how animal and plant populations will be affected by further stress is often uncertain. A good place to start, then, is to take stock and record what we have right now. This can be a painstaking process for individual animals, which often require collection and tagging. But satellites are well-suited for keeping tabs on more visible and stationary lifeforms, like forests and corals. |

|

|

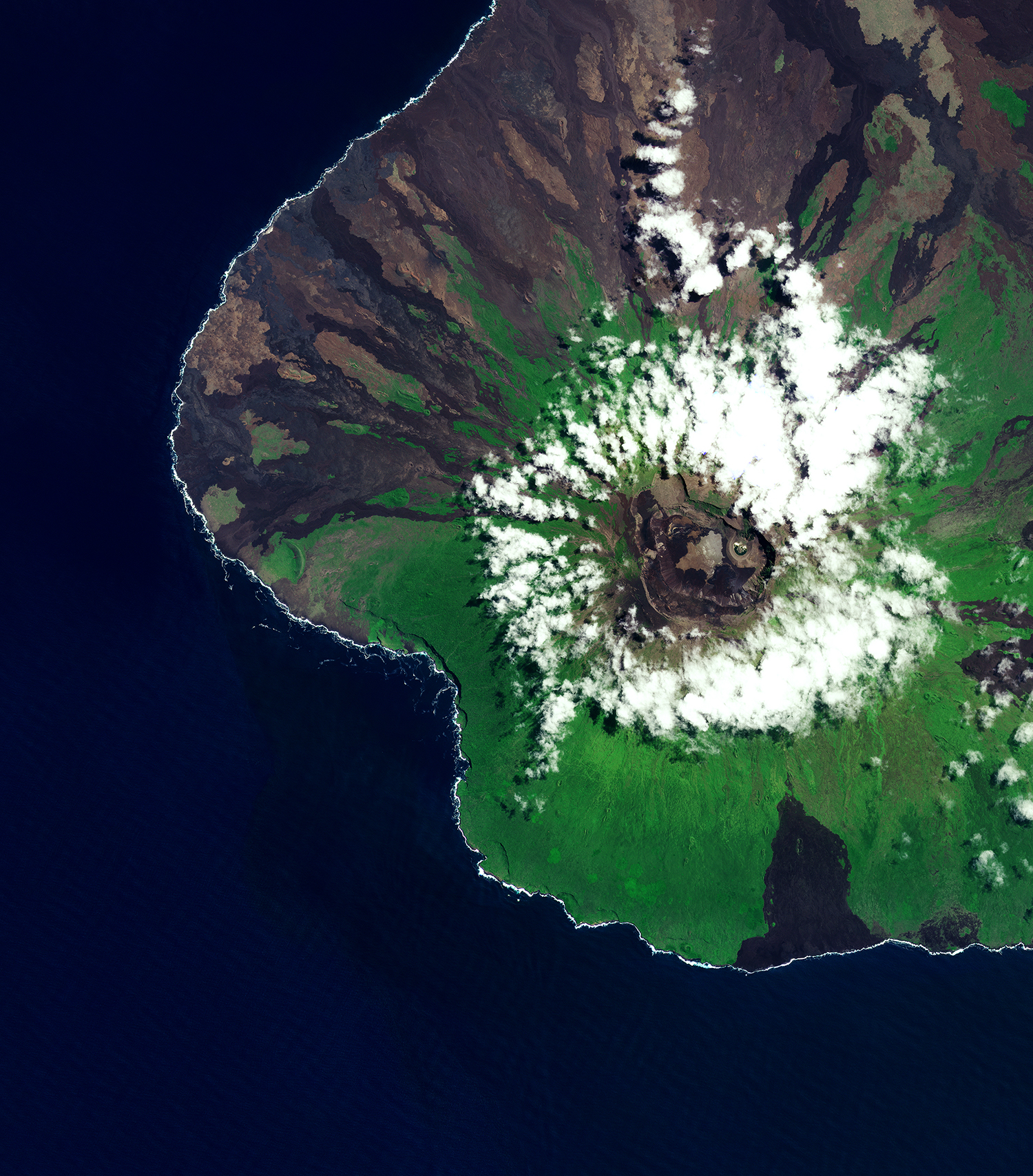

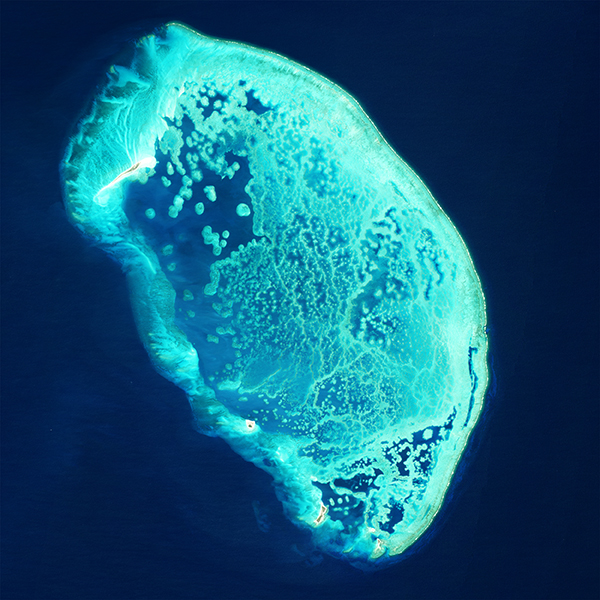

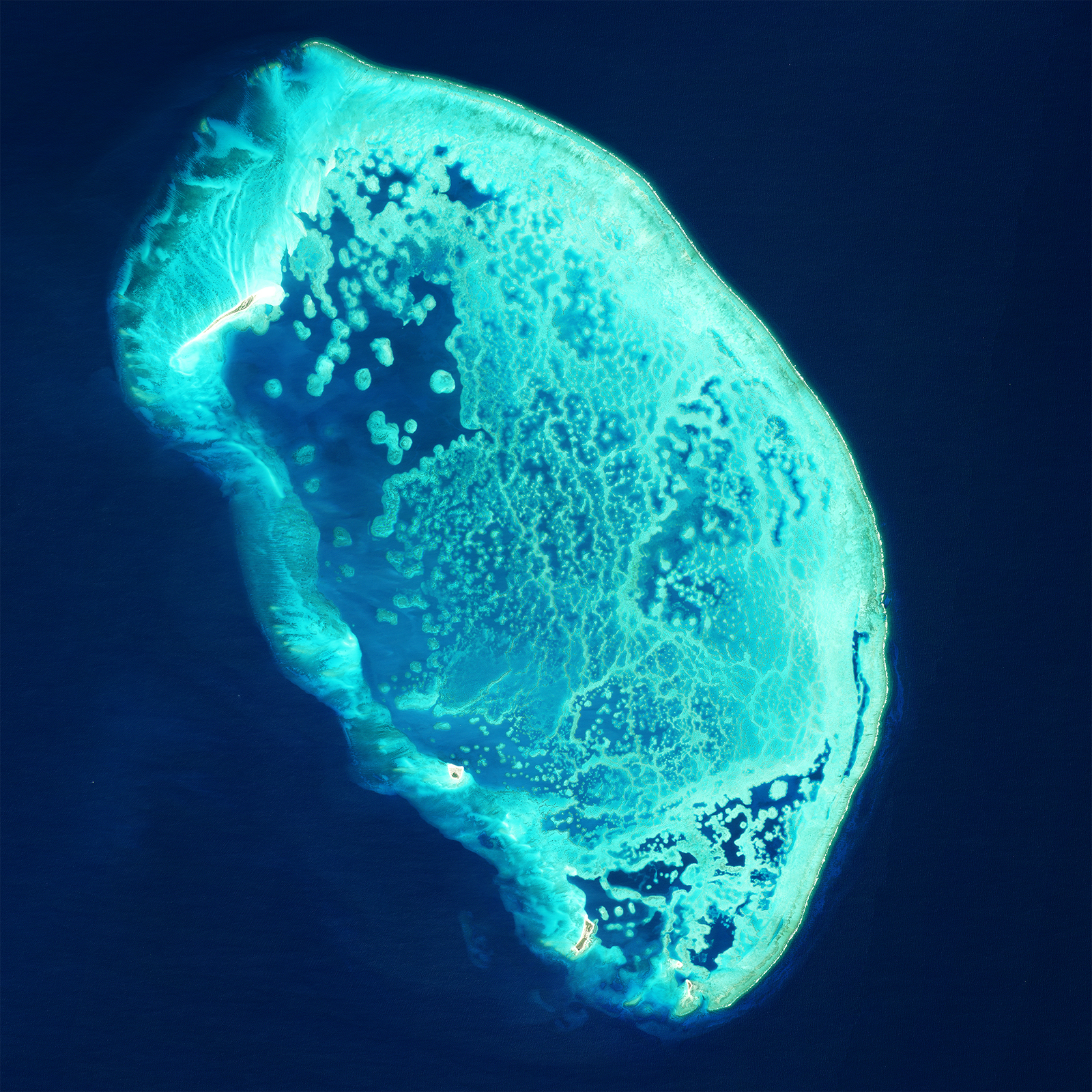

PlanetScope • Scorpion Reef, Gulf of Mexico, Mexico • February 25, 2023 |

Places like The Nature Conservancy are using satellite data to create detailed maps of the Earth’s coastal ecosystems. Having them mapped and monitored can then let researchers know whether these critical areas—and all the benefits they provide—are in decline or rebounding. And the same can be done for other large stocks of plant life, like seagrasses in Seychelles. |

|

|

SkySat • Praslin, Seychelles • November 1, 2021 |

With so many unknowns surrounding biodiversity and its loss, it’s best to focus on the areas that are proven to be effective. Across the globe governments are establishing refuges and protected areas as bastions against encroaching danger. But many of climate change’s most devastating impacts can’t be prevented by a border or wall. And as people look to extract more from the world’s resources, even tepuis—table-top mountains—in national parks aren’t safe from development. |

|

|

|

PlanetScope • Mining around and on top of a tepui in Yapacana National Park, Venezuela • March 22, 2023 |

For conservationists, however, diversity is the key word in biodiversity. Certain species populations, like chickens and corn varieties, have grown explosively under an anthropogenic regime. And as climate change alters the chemical composition of our oceans and atmosphere, some species are primed to thrive. MIT researchers recently used satellite data to discover that over half the ocean has turned greener since 2002, likely due to the increasing prevalence of phytoplankton. |

|

|

PlanetScope • Phytoplankton bloom in the Gulf of Naples, Italy • June 27 - July 9, 2023 |

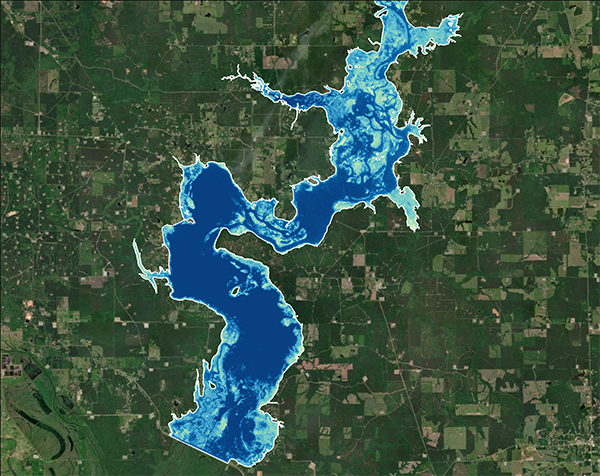

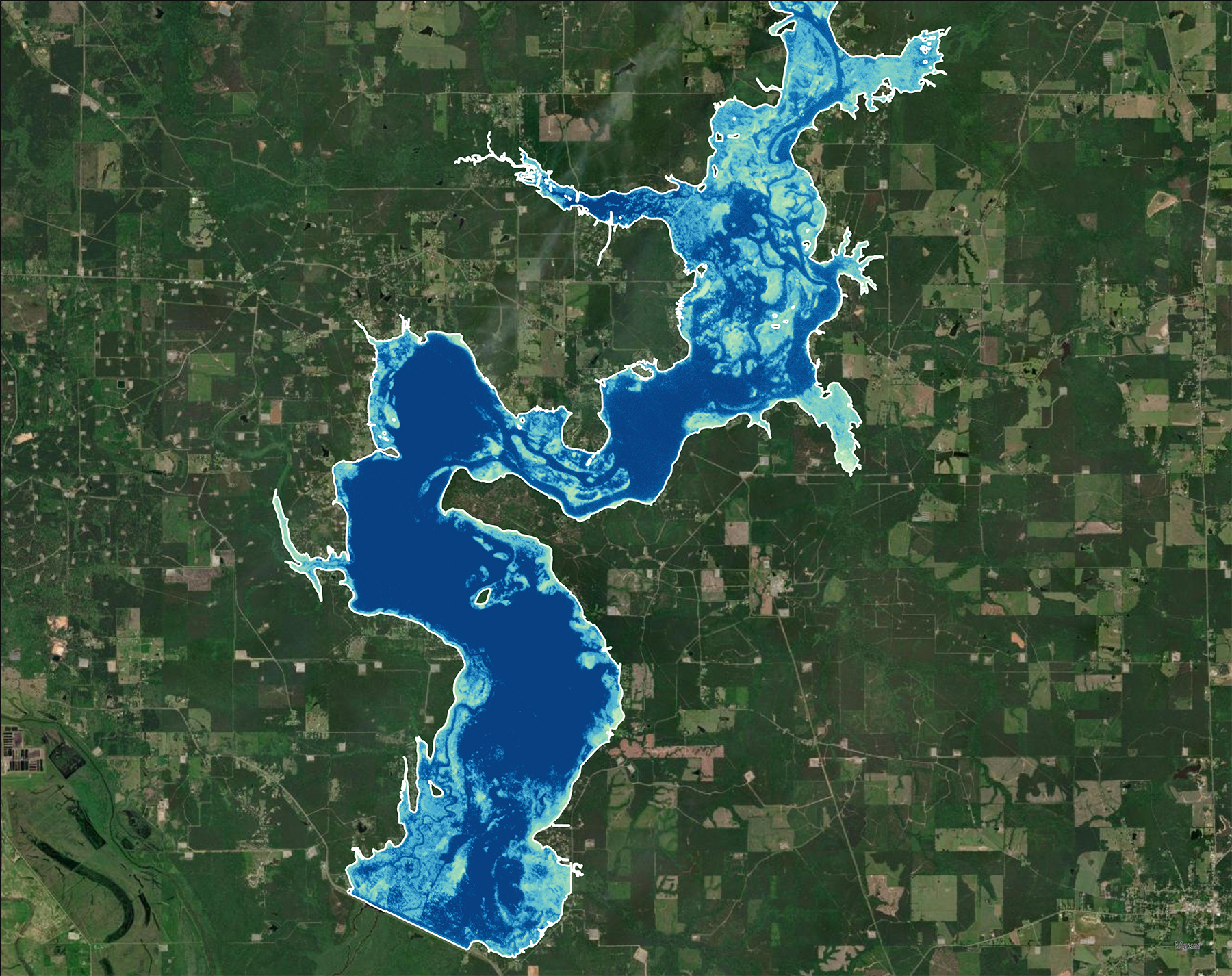

As climate change redraws the distribution of species, migration patterns, and habitability, conservation efforts are increasingly concerned with invasive species. Those hoping to limit their spread are turning to satellites, which can use NIR sensors to detect unwanted vegetation and help with eradication efforts. |

|

|

PlanetScope (NIR) • Lake Bistineau, Louisiana, USA |

The environmentalist John Muir once spoke of any individual thing being hitched to everything else in the universe. That’s a good reminder when gazing at Earth from outer space. Often the planet’s most biodiverse areas appear uniformly green. But look a little closer and the web of life takes shape. We’re a part of that web. And we’re discovering, slowly, that when we tug on one thread, it’s hitched to everything else. |

|

|

PlanetScope • Mount Lawu, Indonesia • September 17, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WHAT IN THE WORLDTepuis

If you’d like to dine with the gods, the best spot would probably be the table-top mountains of South America, called tepuis. But be warned: pulling up a seat is no easy feat. Over a hundred of these mountains rise between 1,000 and 3,000 meters (3,280 and 9,840 feet) from the rainforests below. The sheer cliffs of the tepuis, meaning “house of the gods” in the local Pemon language, create isolated ecosystems separate from the forest floor. Various endemic species found nowhere else live atop these biodiverse islands in the sky. They’re older than the Andes and have a shared past with West Africa, back when the continents were one. In fact, many of its species and minerals are closely related to ones from across the sea. |

|

|

SkySat • Angel Falls, Canaima National Park, Venezuela • March 23, 2023 |

|

|

PlanetScope • Angasima-tepui, Venezuela • May 5, 2023 |

|

|

PlanetScope • Mount Roraima, Venezuela/Brazil/Guyana • March 14, 2023 |

Though not technically a tepuis (since it’s located in Africa), we’re including this other table-top mountain because it’s a great image with an even better story. A researcher spotted this pristine forest on Google Earth, Mount Lico, and led a team to study its time capsule environment. Locals obviously knew about the mountain, but its steep cliffs made it nearly impossible to access. |

|

|

SkySat • Mount Lico, Mozambique • March 15, 2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

Weekly Revisit

Last week we took to the high seas to explore how high-flying satellites and AI are changing the maritime domain awareness game. So check it out in case you missed it and read more stories at the full archive if you’re extra curious. |

|

PlanetScope • People’s Liberation Army Navy Exercises • April 1, 2018 |

|

|

|

|