|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

February 23, 2023 | ISSUE 64 |

|

|

|

SkySat • Burrup, Australia • November 21, 2020 |

In this week’s issue:

The beauty and value of wetlands The remains of a Saharan lake A 61-mile line in the sand Huge icebergs from the Doomsday Glacier Having trouble viewing images? Then read this issue on Medium! |

|

|

|

|

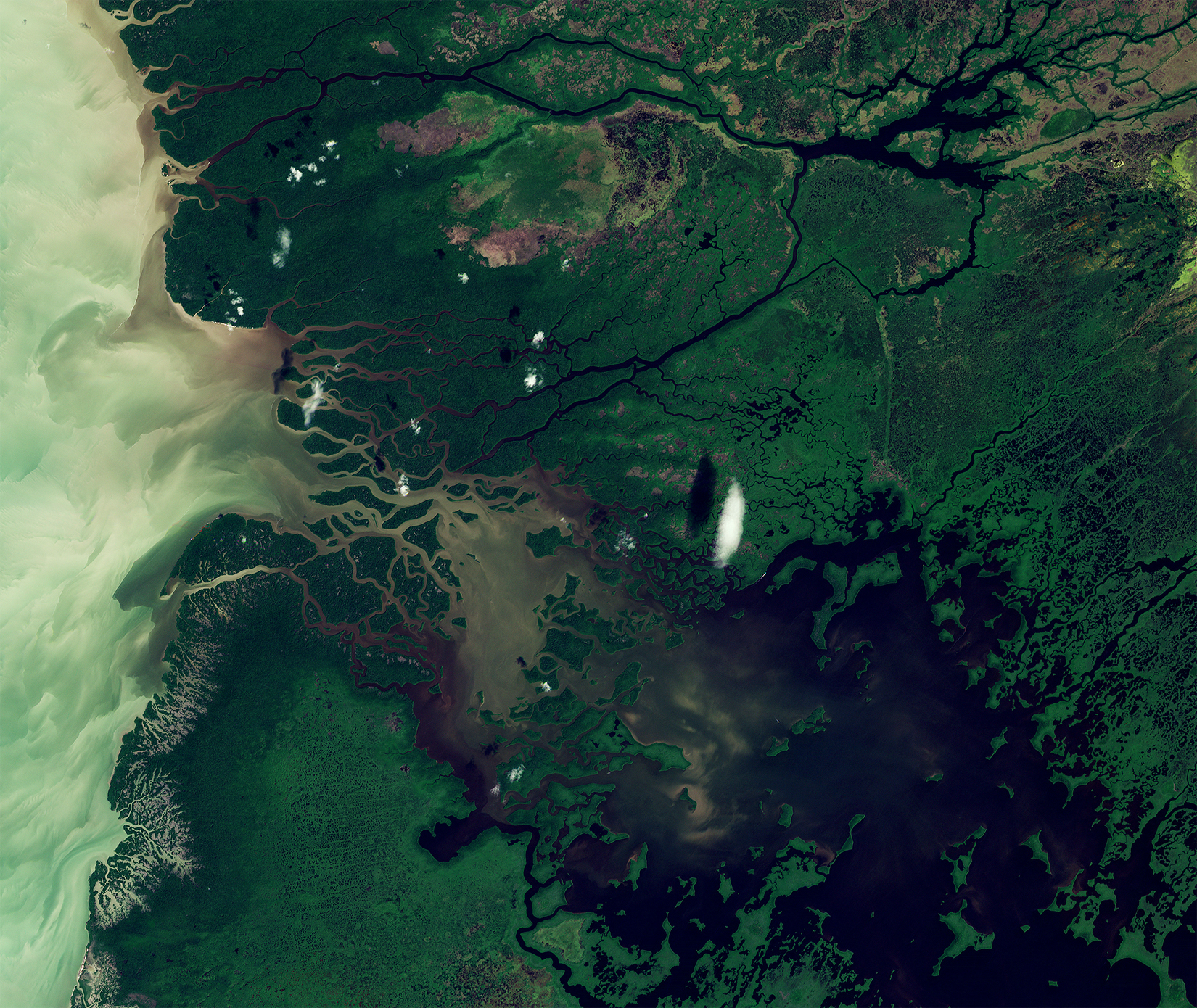

FEATURE STORYWetlands

Wetlands are like the amphibian class of landscapes. They’re ecosystems where water either floods or saturates the land, sometimes permanently, sometimes seasonally. Like frogs (which love wetlands), these areas exist somewhere between wet and dry states. But in many respects they’re the unsung heroes of the ecosystem world, with their enormous benefit to human and animal populations often overlooked.

Wetlands are an umbrella term for a whole slew of water-inundated landscapes. There’s the big 4 (marsh, swamp, bog, and fen), but also peatlands, sloughs, mires, billabongs, and many other fun-to-say terms. Not to mention further classifications like tidal wetlands, estuaries, and floodplains. They’ve got more aliases than a covert spy, yet they don’t garner as much media attention as some of their flashier ecosystem counterparts. So this week, we’re shining a light on the diverse types and functions of wetlands.

|

|

PlanetScope • Lake Chad, Chad • June 23 - August 4, 2022 - January 15, 2023 |

Overwatering your houseplant doesn’t make it a wetland—they’re more than wet soil. Wetlands are broadly characterized by water source (ocean, river, or groundwater) and the type of plant species they support. For instance, swamps are wetlands with woody vegetation, while marshes support emergent vegetation like cattails and water lilies. Wetlands in all their forms are found on every continent and an estimated 300-400 million people live in close proximity to them. |

|

PlanetScope • Keep River mangroves, Australia |

Wetlands are a gold mine from an ecological and economic standpoint. They support 40% of all plant and animal species despite covering just 6% of Earth’s land surface. But perhaps wetlands’ most valuable asset is their sponginess. Give a wetland polluted and waste-ridden water and they’ll return it purified. Their slow water flow and biodiversity richness make these ecosystems simple and effective water treatment facilities. |

|

PlanetScope • Coringa Wildlife Sanctuary, India • August 25, 2022 |

Storm surges, rising tides, and extreme flooding events have communities around the world seeking solutions to fortify their coasts. Many places have long known that the best solution is often the simplest: wetlands. These water adapted environments are excellent at absorbing excess water and preventing coastal erosion. In many instances, protecting coastlines is simply a matter of protecting wetlands. |

|

PlanetScope • Everglades National Park, Florida, USA • October 8, 2022 |

As we rush to figure out a way to pull all the carbon we’re releasing into the atmosphere back into the ground, wetlands once again offer a simple solution. These ecosystems are effective carbon sinks. Peatlands alone store twice as much carbon as all the world’s forests combined—and that’s just one form of wetland. The problem is that this goes both ways: what can be stored can also be released. And with wetlands disappearing rapidly, there’s ample room for concern. |

|

PlanetScope • Southern James Bay, Canada • October 11, 2022 |

An estimated 87% of the world’s wetlands have been destroyed or converted over the past 3 centuries. And recent studies have found they’re disappearing 3 times as fast as forests. The more we lose, the less biodiversity Earth can support, the more susceptible coastal populations are, the more complex infrastructure needs to be constructed, and the more carbon released. As costly climate adaptation strategies are developed globally, preserving and expanding wetland areas increasingly seem like a sound investment. |

|

|

|

PlanetScope • Mekong River Delta and Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam • February 2, 2022 |

Despite offering a simple, natural solution that benefits practically every party involved, this largely silent destruction continues. Perhaps it’s because of wetlands’ lack of attention in popular media. Forests have Smokey the Bear and Arctic ice has polar bears on melting icebergs. But there’s no visual moniker or sympathetic bear to highlight wetlands’ plight. Plus they’re hard to explore without one of the 3 B’s (boat, boardwalk, or big ol’ stilts). Yet their tremendous value warrants a more positive perception, and we hope the tides turn soon. |

|

PlanetScope • Alaska, USA • June 20, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

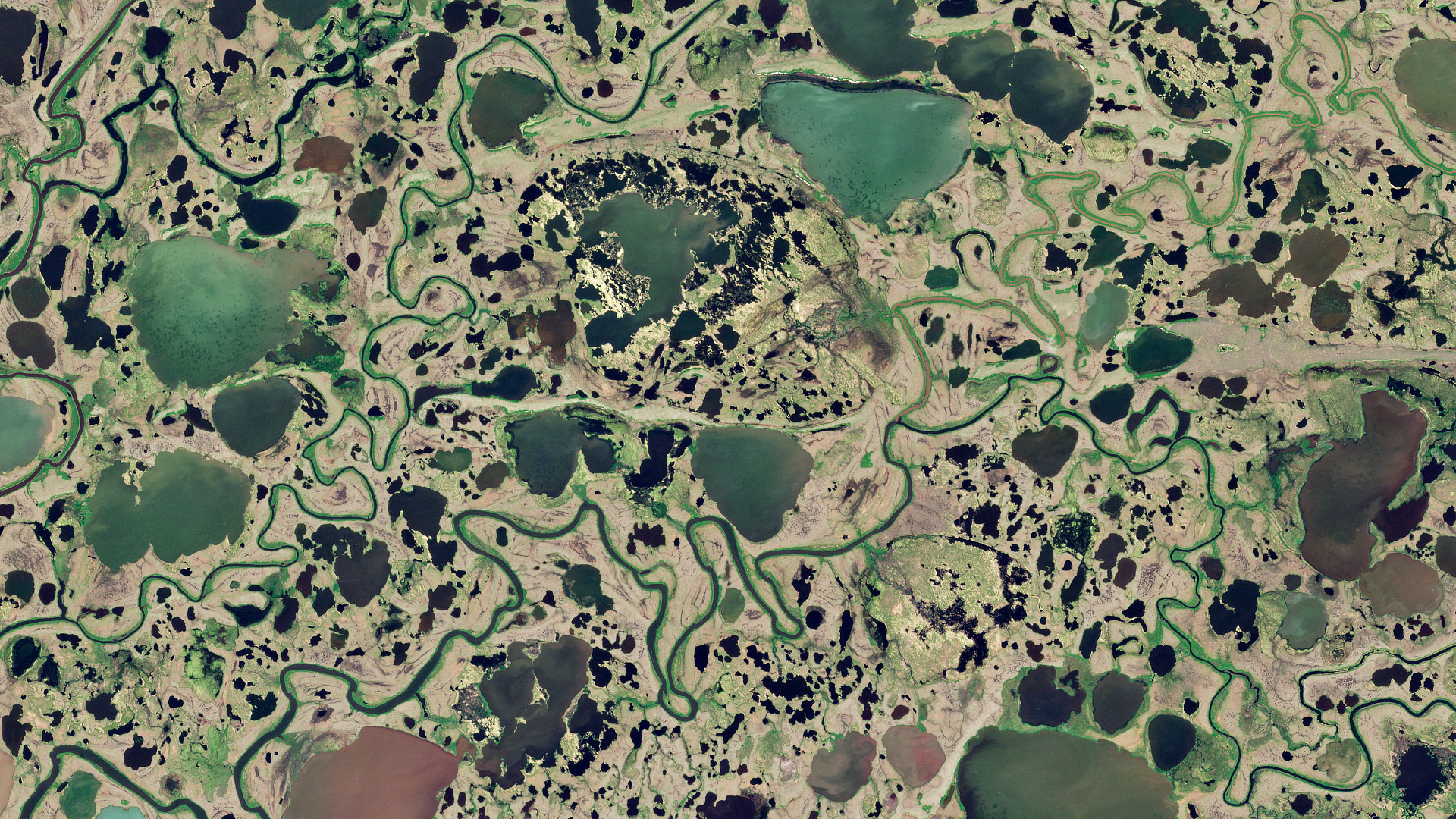

Remote SensationsAncient Remnant

What is is not always what was. These fingers of water are part of the last remaining vestiges of a giant lake that stretched across the Sahara Desert millennia ago. While this region now receives little rainfall and any water rapidly evaporates, these lakes are fed by an underground aquifer and have reed mats (the green coverings) to help with retention.

|

|

SkySat • Ounianga Lakes, Chad • February 9, 2023 |

|

|

|

|

|

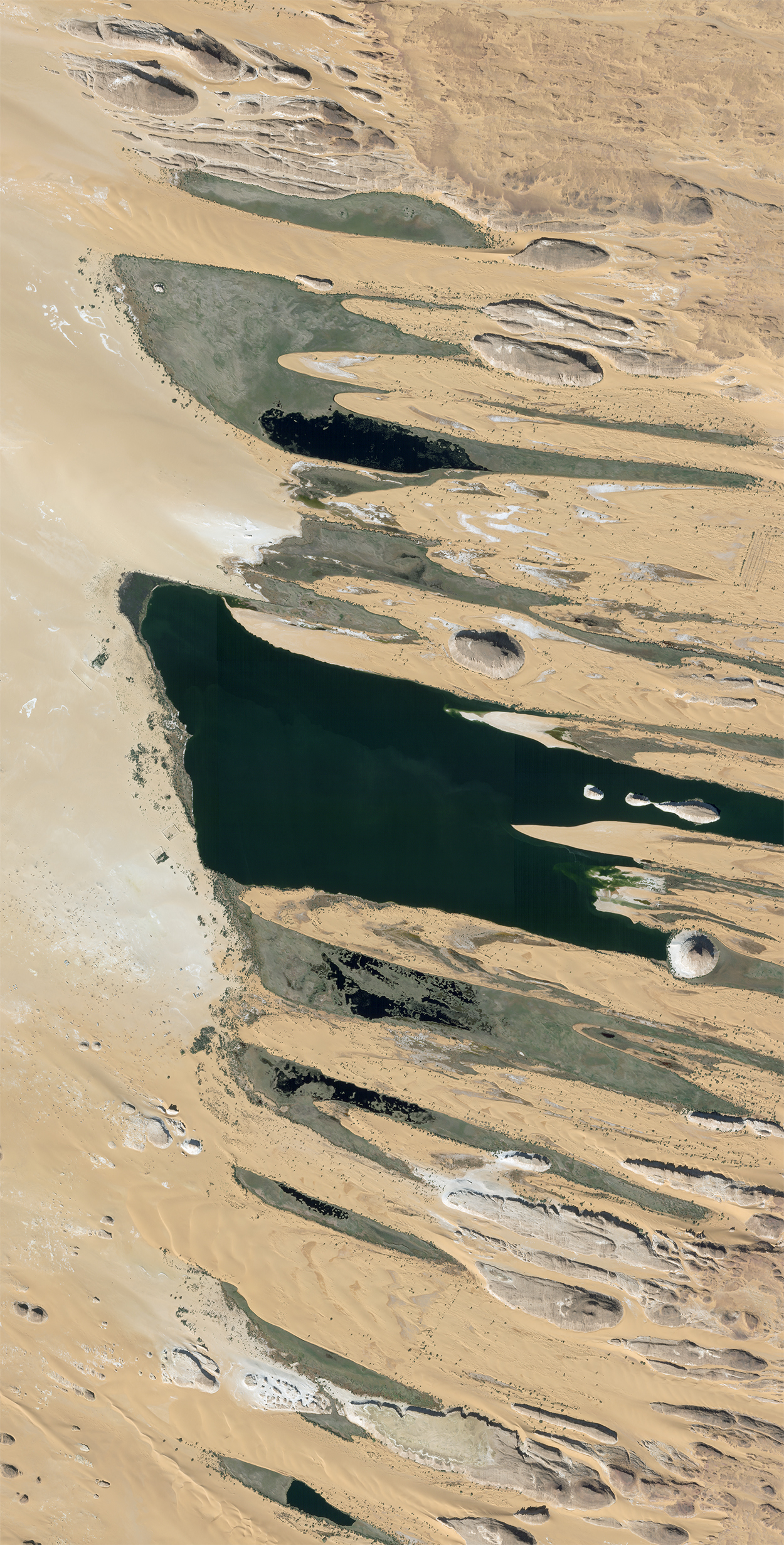

What in the WorldBig Belt

Strangely enough, the world’s longest conveyor belt is another sign of the Sahara’s distant past. The 61-mile (98-km) belt connects the Bou Craa phosphate mine (lower right) to the coastal town of El Marsa (top left), where the mineral vital for agricultural fertilizer is shipped. During its journey wind blows some of the mineral off the conveyor belt and leaves behind a line in the sand distinctly visible from space. Phosphate deposits like these are formed by ancient marine deposits, meaning the large supply found here in the Western Sahara likely formed during its former life as a body of water. |

|

PlanetScope • Western Sahara • December 22, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

|

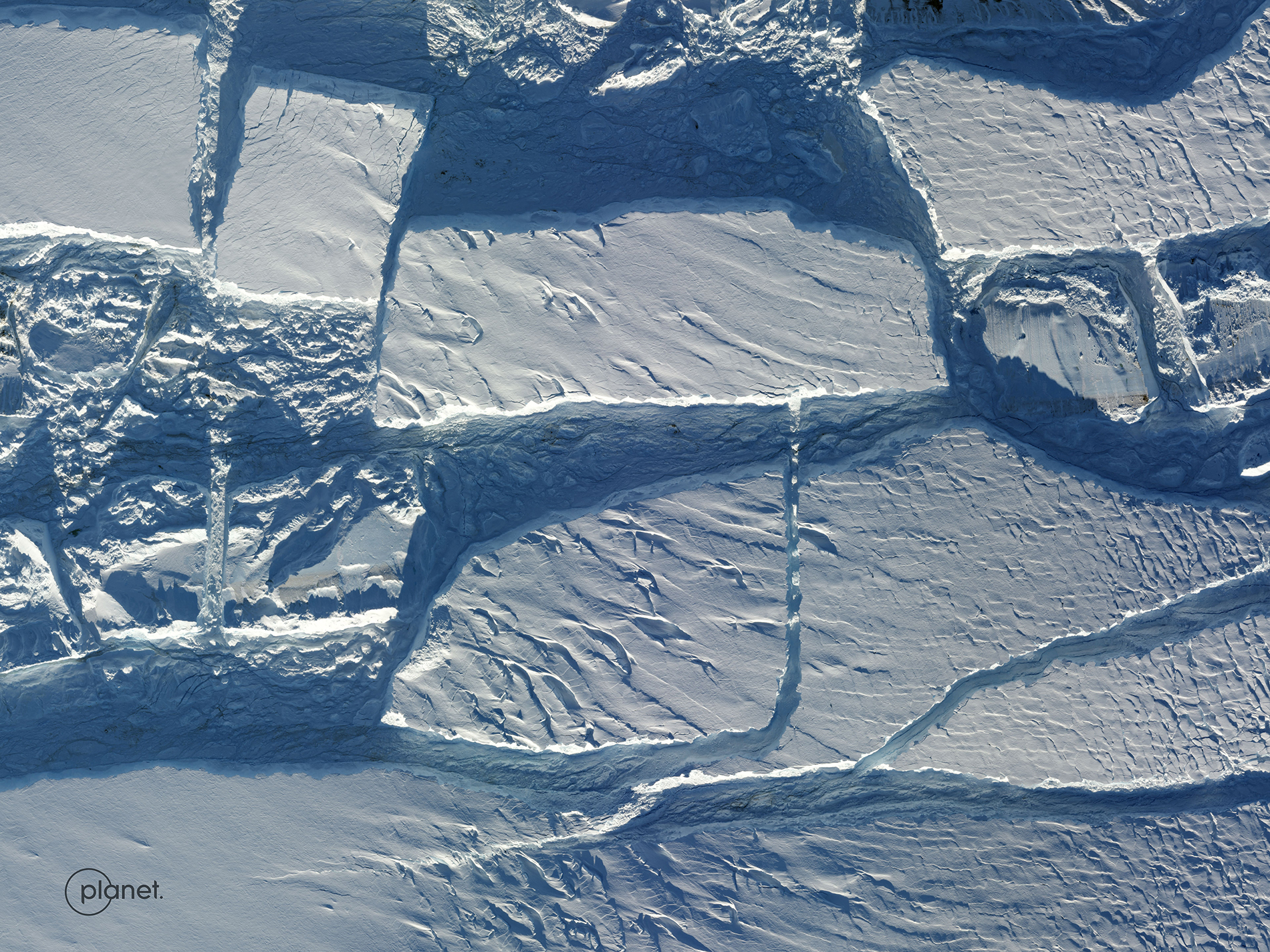

In the NewsGlacial Hunk

News concerning the “Doomsday Glacier” (aka Thwaites Glacier) is hardly ever cheery. Scientists are particularly interested in it because of its contribution to sea level rise (currently about 4% per year) and its potential domino effect if it collapses. A recent study that sent robots and equipment to the bottom of the ice shelf found that the retreat was slower than estimated, but that the melting is more complex than previously thought. What we see from the top, though, are calving icebergs each more than a kilometer (3,280 feet) across.

|

|

SkySat • Thwaites Glacier, Antarctica • December 21, 2021 |

|

|

|

|

|

Weekly Revisit

Last week we explored some extreme environments at the fringes of Earth that scientists use to study conditions on other planets. So check it out in case you missed it and read more stories on the full archive if you’re extra curious. |

|

SkySat • Dallol, Danakil Depression, Ethiopia • January 29, 2023 |

|

|

|

|