|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

January 12, 2023 | ISSUE 58 |

|

|

|

SkySat • Perito Moreno Glacier, Argentina • November 26, 2022 |

In this week’s issue: Satellite data helps forecast future events; a sea of plastic covers agriculture; sediment swirls around a volcano; and Flock 4y shares first light images.

Having trouble viewing images? Then read this issue on Medium!

|

|

|

|

|

FEATURE STORYForecasting

You can be pretty sure the sun will rise tomorrow—for the next few billion years at least. But predicting the future becomes exponentially more difficult (and usually outright impossible) when a system or set of conditions gets more complex. From prophetic oracles of yore to today’s stockbrokers galore, clairvoyance stands as the holy grail of any industry. But anyone who claims to know what the future holds is either foolhardy or an old friend caught up in a pyramid scheme.

That’s not to say the future is entirely opaque. There are some patterns underlying the structure of our world. And rapidly advancing technology can help reveal these logical threads, turning the notoriously tricky business of premonition into (somewhat less tricky) probability maps of potential future outcomes. Satellites contribute to this transformation by providing global, consistent, and timely data that can inform forecasts—from weather to pandemics.

So here’s a few ways in which satellite data—often paired with other datasets—can spot patterns ahead of time and model possible future events. |

|

PlanetScope • Home of the Oracle of Delphi: Delphi, Greece • July 28, 2022 |

Let’s start off with a relatively easy example. Like an angry cartoon character steaming from the ears, volcanoes often release gas before erupting. Satellites often spot venting and other indicators—like lava dome growth and collapse—early in the process and can alert authorities. The unencumbered satellite perspective especially helps for hard-to-reach and hard-to-see volcanoes like the high-elevation Sabancaya volcano in the Peruvian Andes. |

|

SkySat • Sabancaya, Peru • July 8, 2020 |

A probable motto for illegal loggers is “you can’t clear-cut what you can’t get to.” This is especially true for heavily forested areas like the Congo or the Amazon. Roads provide access to loggers but also provide clues to the researchers searching for illicit activity. The “fishbone pattern” emerges when sections of forest are cleared along a road and, if spotted early on, could indicate the presence of logging. |

|

RapidEye & PlanetScope • Realidade, Brazil • 2010 - 2021 |

|

NASA/USGS Landsat & PlanetScope • Matupá, Brazil • 1975 - 2021 |

Predicting the location, time, and severity of catastrophic weather events is difficult and further exacerbated by the uncertainty of a changing climate. But identifying at-risk areas beforehand is easier. Specialists can use satellite data to create flood risk maps—like the one shown here of Bangui in the Central African Republic—to model where infrastructure might be vulnerable to future flooding. A 2019 study shows which detected buildings were found to be in a high-risk flood zone, colored in light blue. |

|

Building detection on Planet Basemaps • Bangui, Central African Republic • 2019 |

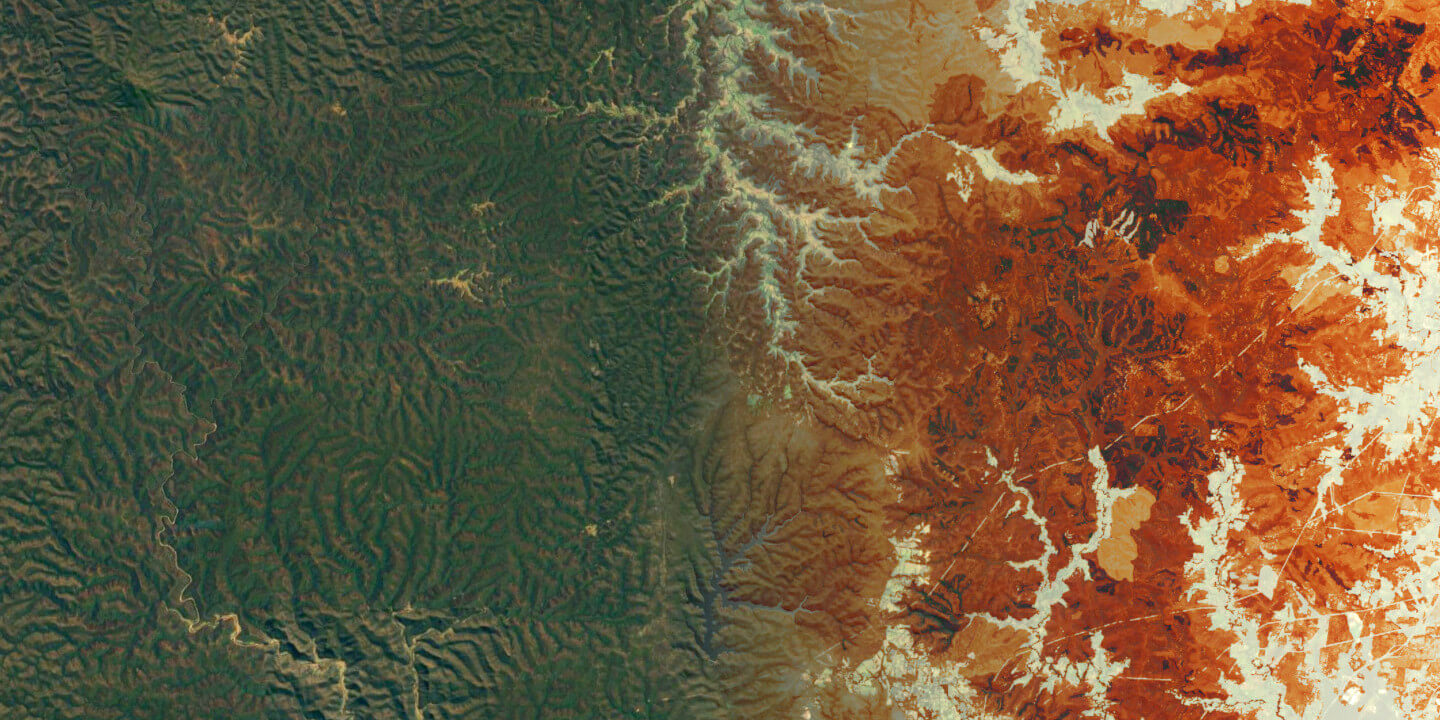

Modeling at-risk areas extends to wildfire behavior as well. Though inherently unruly, fire requires fuel. Map the fuels and a picture of wildfire risk takes shape. Researchers at Salo Sciences combine fuel data derived from satellite imagery with hourly weather data to identify hazards and help communities manage vulnerable areas. This map demonstrates how raw satellite imagery (left) conceals the variation in vegetation fuels (right) across landscapes, with darker reds representing higher fuel loads. |

|

Wildfire Hazard Map • Raw data on the left, vegetation fuels on the right • Salo Sciences |

Forecast models eat data like cows eat grass. The more data, the better the output probabilities. The agricultural industry is one of the largest and most complex systems on Earth. Its inputs are affected by an incredible number of factors and its outputs influence global markets and livelihoods. Modeling the entire system is impossible, but statistical predictions can be made for the yield in some areas. Measurements collected by satellites—like soil water content, temperature on land, and vegetation density—can provide insight into the overall yield. |

|

|

PlanetScope • A fire burns amid center pivot irrigation fields in Toshka, Egypt • May 12, 2016 |

In international conflict, a state’s intelligence is a vital asset. And predicting an adversary’s next move is coveted information. The rise of open-source intelligence has changed how conflicts unfold in the 21st century. Greater visibility into another state’s actions can reveal intent—like the presence of troops near a border before invasion. |

|

SkySat • Yelnya, Russia • October 12 - December 29, 2021 |

Satellite data can help measure the spread of a disease via proxy indicators: a way to indirectly measure an outbreak through associated impacts. For example, diseases originating in animals are more likely to jump to humans when populations are in close contact, often where humans are altering the landscape—a change easily seen by satellites. And in the wake of a pandemic, satellite data can track the movements of goods through ports as a measure of economic vitality, predicting the pace of a region’s recovery. |

|

SkySat • Empty Yingwuzhou Yangtze River Bridge, Wuhan, China • January 28, 2020 |

A lot of the stories we share at Snapshots are reactive—responding to something of the past. But we find it interesting to explore all the ways in which the same data can be used to look forward. No model of a system will accurately predict its outcomes (for now, at least). But data-driven forecasting can help narrow the scope of future possibilities and highlight probable results. It’s not quite as effective as pondering a crystal orb, but it’s far better than shaking a Magic 8 Ball. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Macroplastics

Though not an actual forecast, a small section of Spain’s southern coast may hint at what the future of farming looks like. Welcome to Almería, aka the “Sea of Plastic.” Here, food is pre-packaged in plastic greenhouses that cover an estimated 40,000 hectares (150 square miles) and serve as an important source of off-season produce. As it turns out, plastics are increasingly finding themselves not only in our food but surrounding it as well, whether by greenhouses or packaging.

|

|

SkySat • Almería, Spain • January 4, 2023

|

Greenhouses trap heat—it’s why we’ve dubbed the process that’s warming Earth as the “Greenhouse Effect.” So in an ironic twist, the greatest concentration of greenhouses on Earth is so vast it’s actually cooling the local region by reflecting sunlight away. |

|

PlanetScope • Almería, Spain • November 29, 2021 |

|

|

|

|

|

What in the WorldSediment Swirl

The only thing we like more than cool volcanic islands in the middle of the ocean are ones with spirals around them. Discolored water enchantingly swirls around Nishinoshima, a Japanese volcanic island about 1,000 km (621 mi) south of Tokyo. |

|

SkySat • Nishinoshima, Japan • December 2, 2022 |

|

|

|

|

|

Weekly Revisit

Last week we did a brief behind-the-scenes of the first launch of the year—a bright, loud, and incredible affair. We had 36 satellites onboard, and the flock just shared its first light images. So here’s two of ‘em. And check out the whole Snapshots archive if you want to learn more about what these little powerhouses can do.

|

|

Flock 4y First Light • Wexford Harbor, Ireland • January 9, 2023 |

|

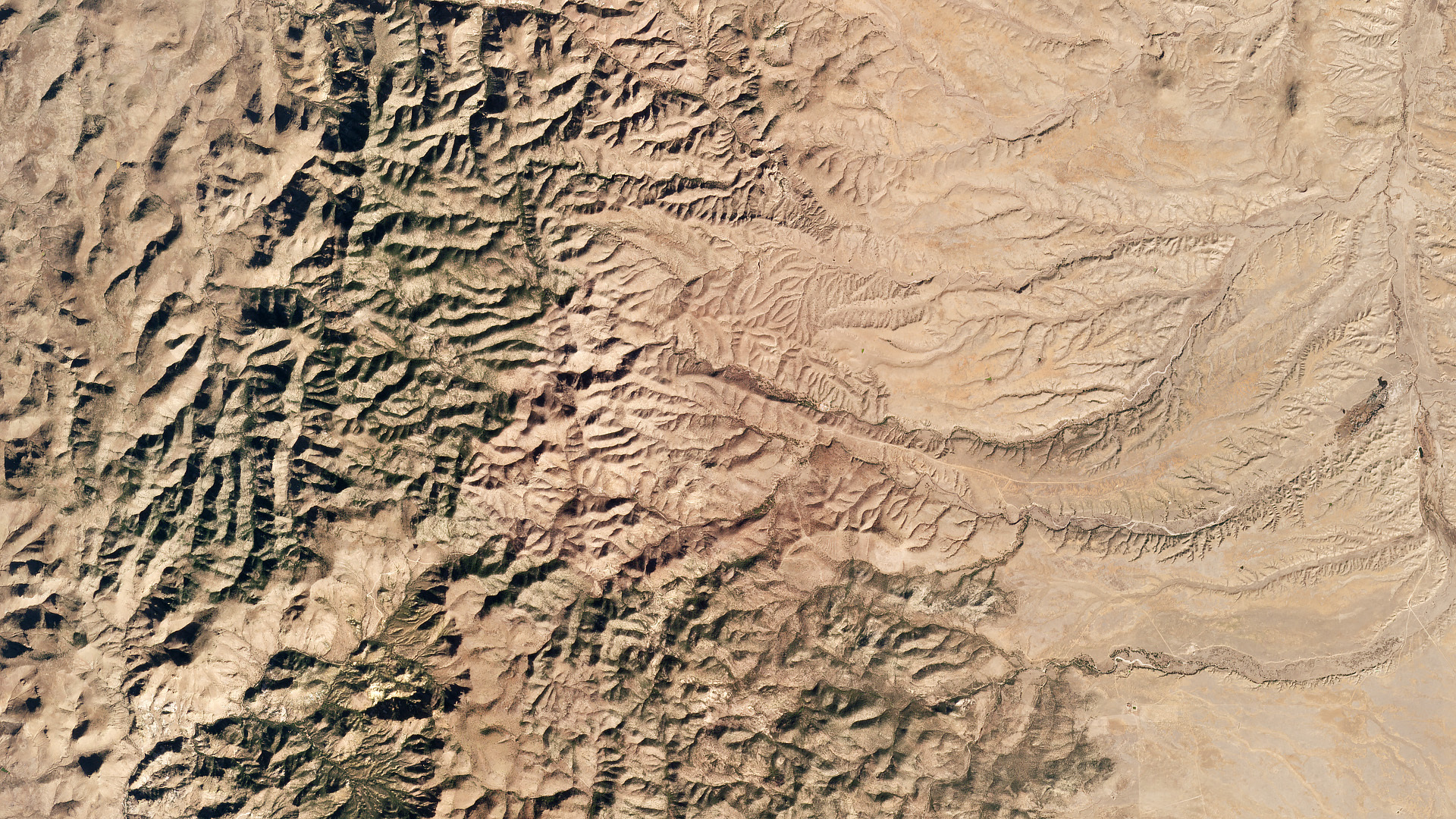

Flock 4y First Light • Whitmire Canyon, New Mexico • January 9, 2023 |

|

|

|

|